On September 22, the Centre Pompidou closed its doors for renovation. Located in Paris, the museum hosts one of the world’s largest collections of modern art. In late 2023, I went to the museum, curious to see a specific work of art that featured self-harm. Little did I know it would be the first and only time I’d see it for seven years: the Centre Pompidou will only reopen in 2030.

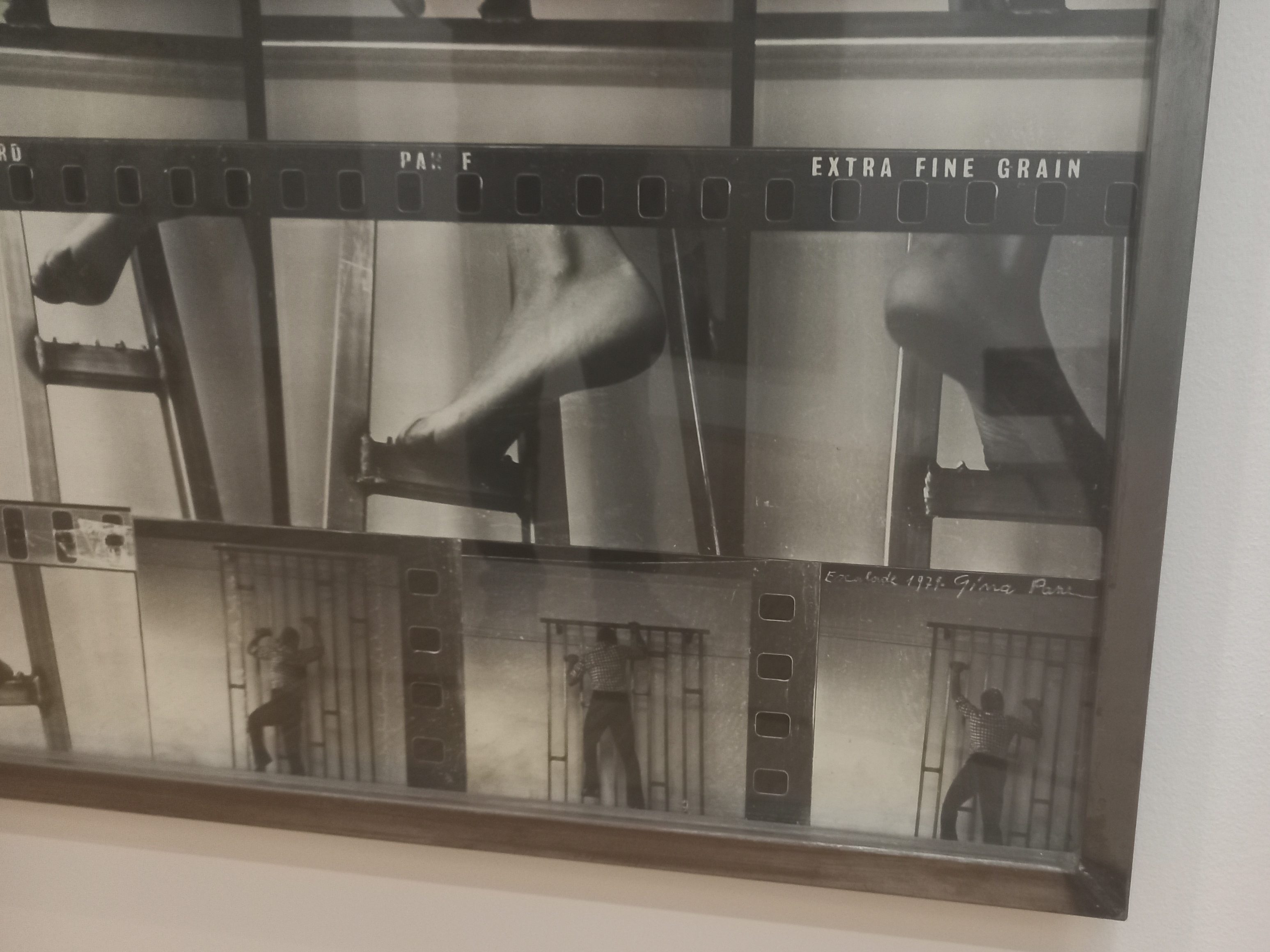

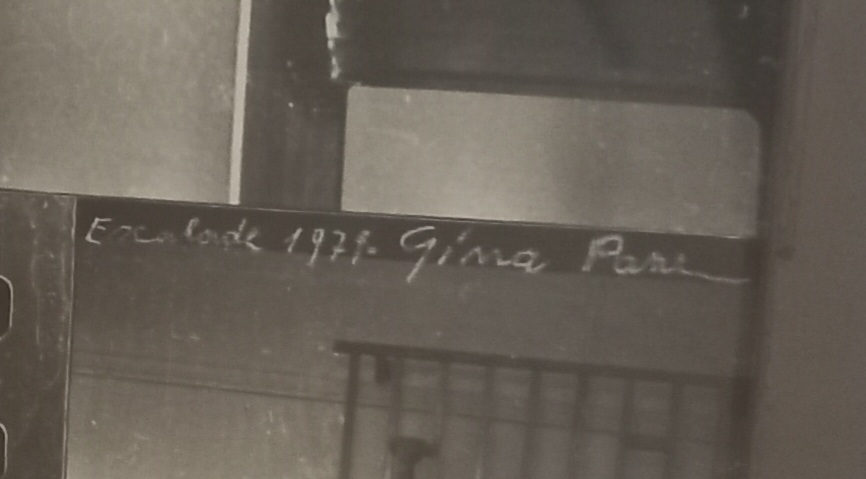

Self-harm in art is very distinct from non-suicidal self-injury. Here, harming the self isn’t a way to cope with mental health difficulties, and we must be careful not to jump to conclusions about the psychological states of artists. Nevertheless, in both cases the body is used to reflect on issues – at a societal and at a personal level respectively. This is the reason why it was used in the work in question by French artist Gina Pane (Biarritz, 1939; Paris, 1990), a renowned figure of body art. Throughout her career, Pane used her body as a material to explore the theme of suffering1. In April 1971, she performed the artistic piece “Action Escalade non-anesthésiée” in front of a small audience in her workshop. Barefoot and bare-handed, she climbed a ladder whose rungs were equipped with sharp metal shards. She was photographed doing so by Françoise Masson2,3. The work was the first of a series she performed and then displayed in the form of photographs2.

But the work of art isn’t the performance itself. It combines a series of photographs documenting the performance, with the actual ladder used. Gina Pane initially intended to also exhibit a bloody bandage, but the ridges were not sharp enough, and didn’t draw blood on either her hands nor feet. Looking at the photographs only, we wouldn’t know the performance was actually harmless. The photographer used close and low-angle shots to give the impression that the climbing was more painful than it really was.

But observing the real ladder, we can put the performance into perspective, and see that the shards aren’t actually very dangerous. Pain is very subjective, and no one can ever really understand how others experience it. In her following work, Gina Pane would not exhibit the objects used in her performances, perhaps to avoid diminishing the shocking value2.

But why did Pane seek to shock us? The use of suffering in her work was obviously provocative, but it wasn’t done merely for aesthetic reasons or to entertain. By shocking the viewer, she was trying to send a message3, a message that the title of the work helps us understand.

“Action Escalade non-anesthésiée”. The French word “escalade” has a double meaning: climbing, and the escalation of a conflict. Gina Pane drew a parallel between her climbing on the ladder and the escalation of the war in Vietnam2. “Unanesthetized” refers to her experience of pain in the performance, but also to the state of the viewers. Pane believed society had gotten so used to violence that it wasn’t shocked anymore by the war in Vietnam, becoming in a way “anesthetized” to the pain caused by the conflict4. And yet, the view of a western woman painfully climbing this ladder right in front of them was shocking to them, they were “unanesthetized” to this type of pain – despite the fact it was willingly endured by the artist for her art.

It was by stressing the contrast between indifference to extreme suffering across the globe, and mild pain in front of the viewer, that Gina Pane sought to raise awareness3.

Gina Pane wasn’t the only one who used self-injury to comment on the war in Vietnam. In 1971, American artist Chris Burden got a friend to shoot him in the arm. Faced with unprecedented TV coverage of people getting shot during the Vietnam War, this was for the artist a way to comment on America’s fascination for gun culture and violence. Given people see others getting shot, comfortably and passively sitting behind their TV screens, Burden thought it was interesting to know what it’s like to get shot. But choosing to get shot, choosing the shooter, the gun, then time and place, and in a way that minimizes any serious harm, can’t be compared to the traumatizing reality of becoming a victim. As Angelica Modabber writes in Synapsis5, “Burden knows what it feels like to get hit in the arm by a bullet, but he still has no idea how it feels to get shot.”

The use of self-harm in art to comment on the Vietnam War isn’t limited to performance art. The device was used in 1967 by future famous filmmaker Martin Scorsese in his student film “The Big Shave”, one of the first films he directed. Picture a man shaving his face in his bathroom. He’s young, white, the typical average American middle-class man. In the background, the jazz song “I Can’t Get Started “ by Bunny Berigan is playing. Suddenly, he accidentally cuts himself. He keeps shaving, cutting himself more and more, before slitting his throat. In just over 5 minutes, Scorsese managed to get the viewer comfortable with a mundane daily ritual, before shocking it with graphic close-ups of blood, while a relaxing song is playing in the background. This contrast was intended to raise awareness about the Vietnam War, seen by the director as a form of self-harm the United States were inflicting upon themselves. The short film was also alternatively titled Viet’ 67. And yet, Scorsese later admitted the film was more about his personal struggle and his vision of death at the time. Similarly to pain, which is very subjective, interpretation of a work remains very personal.

I’ve never been really receptive to performance art, and I’m not sure I would have understood the message of the work without the help of the explanatory sign placed next to it. Its meaning is less obvious now that 50 years have passed since its creation, and we are no longer as aware of the political and historical context of the time. I couldn’t help but find it ironic that a work of art that was originally meant to be controversial is now exhibited in a renowned museum. Kathy O’Dell used to work as a program coordinator for a non-profit art space, and wrote “Contract with the skin”6, which covers the use of masochism and self-harm in performance art of the 1970s. As she explains in her book “[o]ur mission was to present work that commercial galleries and museums would not touch at the time – such as performance art”. Surely things have changed, the subversive has become mainstream, and once marginal and anti-establishment art is now exposed in a public museum which receives state subsidy.

References

[1] Centre Pompidou. (n.d.). Gina Pane – Action Escalade non-anesthésiée. Centre Pompidou. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/ressources/oeuvre/cKaGr5K

[2] Duplaix, S. (2007). Collection art contemporain: la collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne (S. Duplaix, Ed.). Centre Pompidou.

[3] Vazquez, T. (2023, July 19). Gina Pane, souffrir pour l’autre — INITIAL Magazine. INITIAL Magazine. https://initialmagazine.com/initial/gina-pane-souffrir-pour-lautre

[4] Goldberg, R. (2001). La performance: du futurisme à nos jours (C.-M. Diebold, Trans.). Thames & Hudson.

[5] Modabber, A. (2024, April 23). What Can Chris Burden’s Performance Art Tell Us About Gun Violence? Synapsis: A Health Humanities Journal. https://medicalhealthhumanities.com/2024/04/22/what-can-chris-burdens-performance-art-tell-us-about-gun-violence/

[6] O’Dell, K. (1998). Contract with the skin : masochism, performance art, and the 1970’s. University of Minnesota Press.