Trigger warning: this article mentions graphic instances of self-injury and features magazine covers that depict self-injury wounds and scars

On May 15, 1991, the rock band Manic Street Preachers performed in Norwich, England. They had not released any albums yet, but they were already receiving growing media coverage. After the show, they met with NME journalist Steve Lamacq for an interview. Lamacq had never hidden his opinions about the band, which he saw as a marketing product with no authenticity. After half an hour of disagreement, guitarist Richey Edwards grew impatient. He took a razor blade and slowly carved into his arm the term “4REAL”, to prove the band’s authenticity. They initially continued the interview, but since his arm was bleeding heavily, Lamacq called the band’s manager for help. The injury was bandaged, photographed, and Edwards was transported to hospital. There, he received 17 stitches.

The event triggered a polarized debate among the NME staff. They wondered whether the magazine should publish the photographs. Some were excited, claiming it was a great representation of rock culture, but others worried about young fans copying Edwards and harming themselves. Eventually they decided to publish only a small, less graphic version of the photograph on the magazine cover, and include the more graphic images inside the issue. But in 1999, the magazine was less cautious and featured a graphic version of the incident on the cover.

The “4REAL” cover is unusual: it is messy, overexposed, and shocking – a sharp contrast with the fashionable photos of celebrities and models traditionally featured on magazine covers. And yet, another magazine once dared to publish a cover girl with self-injury.

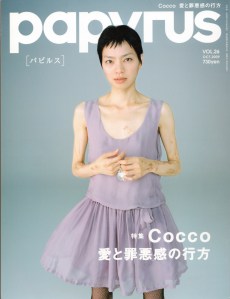

In 2009, Japanese magazine Papyrus featured singer and actor Cocco on their cover. At the time, Cocco was struggling with anorexia and self-injury. The photographer didn’t shy away from capturing her emaciated and scarred body, presenting self-injury as a fashionable body feature: a dozen full-page photographs show her striking poses in stylish clothes, displaying scars, some in the shapes of stars or words.

This is reminiscent of a photograph published in NME just a week before the “4REAL” incident, depicting Richey Edwards and his bandmate Nick Wire with slogans written on their chest: Wire’s with lipstick, Edwards’ carved into his skin. Edwards and Cocco both made self-harm part of their art, by including it in their public image, and mentioning it in their lyrics. Self-injury is for them a symptom of mental health issues, but also a means to self-expression and a way to craft their public image.

While Cocco’s interview in Papyrus adds more context and relates her struggle with self-harm and recovery, the message of awareness is clearly overshadowed by the photographs, raising questions about the magazine’s intentions. Is it trying to raise awareness about mental health issues, or glamorize them for marketing purposes? In that regard, Steve Lamacq’s accusations about Manic Street Preachers’ greed and lack of authenticity could also apply to media’s coverage of self-injury. On numerous occasions, magazines have featured images of Richey Edwards only, instead of the band as a whole, his tortured personality being more profitable for the press than their music.

The use of self-injury to craft a persona is not exclusive to music. The October 1999 issue of Talk magazine features an interview with renowned actor Johnny Depp. And yet, the article doesn’t open by praising his acting talent, but instead mentions the “series of scars-neat little nicks” that journalist Tom Shone notices on Depp’s arm, wounds the actor allegedly inflicted upon himself as rites of passage. “[W]elcome to the wonderful world of Johnny Depp and his amazing self-inflicted knife wounds!”, exclaims the journalist. On the cover of the magazine issue, the title “Johnny Depp Shows His Scars” teases the article. While Depp showed his scars to the journalist, he didn’t to the reader. Photographs depict him bare-chested, but none of them reveal any scars. Perhaps the magazine editor was wary of controversy.

Few similar cases are known, either because they fell into obscurity, or because the press avoided such representation due to stigma. The increasing use of the internet probably didn’t make it easier, enabling any controversy to spread fast. And yet, over the past decade, the visual depiction of self-injury has started to emerge in fashion marketing. From glamorization to attempts at raising awareness, its depiction remains sensitive, and often controversial.

If you found this article interesting and would like to further explore how the media, celebrities, and the fashion industry both raise awareness and glamorize self-injury, I recommend the following articles:

- 4REAL: Richey Edwards and his struggle with self-harm – On May 15 1991, Manic Street Preachers’ Richey Edwards carved the words ‘4REAL’ into his forearm during an interview. Looking beyond the myth of the tortured artist, this article questions the public representation of mental health.

- From self-injury to self-styling: integrating self-injury into fashion – For many people, self-injury means shame and hiding their body. Through styling and fashion, some find the path to self-acceptance. But change is often met with controversy.

- Interviews with photographers Kosuke Okahara and Lin Shihyen – These photographers share how they used their art to humanize those who struggle with self-injury, challenging sensationalist representations of mental health issues.