Trigger warning: graphic descriptions of acts of self-injury

Stigma and social norms pressure most of us into hiding what is not accepted in society. But behind closed doors, within our own home, we are more free to be ourselves, away from judgment. This part of us is rarely seen, and yet this is precisely what Japanese photographer Kosuke Okahara wanted to show in his project Ibasyo, which deals with the theme of self-injury.

In search of Ibasyo

In November 2024 I attended Okahara’s presentation about his series Vanishing Existence at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris. He was fluent in French, having lived there for a few years. There, I got the opportunity to ask him for an interview.

Okahara has documented numerous issues across the world, such as the migrant camps in Calais, the war in Sudan, the impact of drugs in Columbia, or the nuclear disaster in Fukushima. His work focuses on crisis situations, and the concept of Ibasyo, which cannot be easily translated. “Ibasyo is my main theme as a photographer,” Okahara explains. “Ibasyo roughly means physical or emotional space where one can exist, or one can feel he/she is allowed to exist. It can be your family, with your friends, or in your room where you can be yourself, or maybe some online friends you chat with, etc, etc…”.

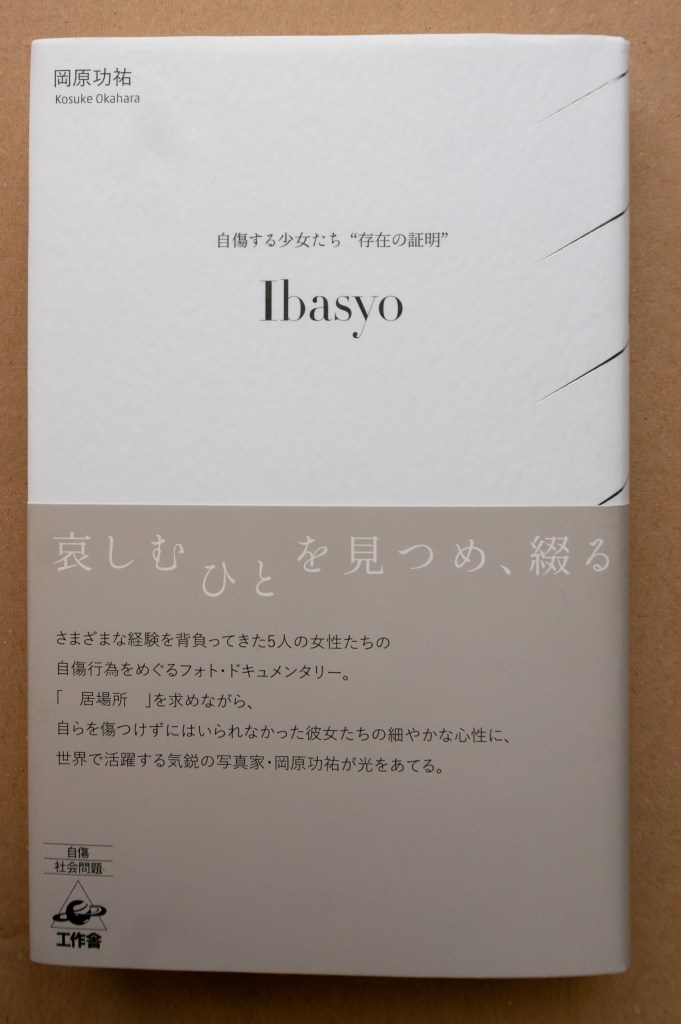

The concept holds such an important place in Okahara’s work that it became the title of his project about self-injury, a topic he felt wasn’t discussed enough in Japan. Much is to be said about the state of mental health in Japan, and to touch upon the societal stigma, Kosuke Okahara chose to focus on individuals’ experiences with self-injury through his photography project Ibasyo, which was later turned into a book. Over the course of seven years, starting in 2004, he met with six women who engaged in cutting, befriended them, and spent time with them to document their story through photography and writing, showing what was kept behind closed doors. Ibasyo is in the same vein as another project Okahara conducted simultaneously, Vanishing Existence, which documents China’s leprosy villages. I mentioned to Okahara that the two projects deal with similar topics, such as stigma, physical marks on the body, and what’s hidden from society, and wonder if working on the two projects simultaneously helped him. “Of course I think well before I start projects but as the projects go, I gain more insight and of course there is some kind of relation among the projects I have been doing as it is eventually me who got interested and conducted the project,” he acknowledges. “I went to China for this project while still working on the Ibasyo project in Japan. So in a sense, the two projects shared similarity. To me it wasn’t so much about stigma, but more like Ibasyo itself. But of course stigma is something very embedded in these two issues without a doubt.”

But while exploring such a complex topic as that of Ibasyo, Okahara warns about the risk of projecting wrong assumptions onto the subject he photographs. “Speaking of Vanishing Existence, the villages I have visited were the physical space where people were forced to live in,” he explains. “But over the years, that became home for people who lived there a long time. This is not the home they wished to live in, but it is hard to deny the existence of those villages as the villages became where they (have to) live. So I believe it is very inappropriate to say either the village became their Ibasyo, or the village was the place where people who were taken away their Ibasyo, like their home town or village, were sent to. I am not the person who can say either of this. Only thing I could do was to recognize people in front of me when I visited those villages.”

Capturing the essence

Okahara’s approach is to be down to earth and spend time with his subjects. Though making people feel comfortable sharing such a private and intimate aspect of them, and managing to take photographs without breaking the flow and spontaneity of meetings must not have been easy. “I think spending a certain amount of time is something I need. So things become normal,” he explains. But even his work method cannot guarantee constant success, as much is left to the subject of the photographs. “Of course some people don’t get used to the camera. So this is not for everyone of the subjects I photograph. Sometimes it is not easy, sometimes it flows smoothly. Honestly speaking, a lot of times it depends on luck too. Like you meet someone and you get along with that person. Sometimes you meet someone whom you don’t get along with… but of course as I am there to photograph, I have to try to read the atmosphere and some kind of invisible chemical reaction with people I photograph.”

Spending so much time with the people he photographs enables Okahara to capture their essence. His choice to shoot in black and white, the way he learnt to photograph, also stems from this desire, as it allows him to avoid thinking too much, in addition to being more accessible than color.

What is too difficult to express

But gaining the trust of the women photographed in Ibasyo came with some responsibility, as each of them has been exposed to, or experienced, traumatizing events and adversities such as depression, domestic abuse, alcoholism, and rape. Okahara himself was far from being unmoved by the despair his subjects endured. “Of course it affects me emotionally. Sometimes it is difficult to deal with it,” he admits. “Sometimes I really have to tell myself that I am here to photograph, not just to feel something and do nothing. In that way I really have to make sure why I am there. It’s like I make sure I am calm while being emotional, but not capsized by the wave of emotion.” It was by focusing on the goal of his project that Okahara could keep working, even when he would witness the girls, which became his friends, overdosing or cutting themselves. “I was very aware that I was there to photograph.” But better understanding the mechanisms behind self-injury also helped him allow the girl to injure themselves, and restrain himself from intervening. “For example, when I saw a girl start cutting in front of me, I actually asked her if there is a way not to harm herself. She said this was necessary to make herself calm. I couldn’t say much but I asked her to promise me that if she feels better, she stops it. She said ok. It was a very strange moment. In a way I felt I was not doing the right thing, which is seeing someone cutting herself in front of me and not stopping her. But I had already spent quite some time with the girl, discussing things, I knew she wanted to do it and she was not going to commit suicide… I have to admit, things didn’t go that bad at that moment. So I was eased when she stopped cutting herself.”

But Okahara didn’t always stick to his photographer role, as he was occasionally forced to intervene and help. “Another time, I had a phone call from a girl and she sounded a little drunk. It was obvious she had overdosed on pills. So I ran to her apartment which is 40 minutes away by train as I didn’t know any friend of hers who could go there quickly. I hesitated for a few seconds to open the door of her apartment. I knocked a few times, and no response. And her apartment door was not locked. I opened the door and I saw her laying down on the floor without consciousness. So I called the ambulance right away and took her to the hospital. In the end, she became fine.”

In trying to help, Kosuke Okahara was also confronted by the discrepancy between the unfortunate experience and desensitization the girls have with self-injury, and his external worried look. “Another time I was actually in the house [of one of the] girl[s]. I was away for like 15 minutes. When I came back the girl was bleeding so much. She actually cut her arms while I was away. It was too much blood. She was spacing out, kind of, but she was aware that she wanted to cut herself, which she said to me. But it was too much blood, something I had never seen before… She said she would do this often. But it was too much for me. I needed to squeeze her arm with clean clothes to make sure the blood stops. Fortunately – she said she knew this would not be too serious, but it looked really serious to me – the blood stopped quickly somehow. I was relieved. I told her to go to the hospital but she refused. I insisted a few times but she refused… in the end she was ok. Though I imagine doing such things over and over again surely damages her body or heart.”

Such stories go to show the level of commitment Kosuke Okahara played in his project, having simultaneously the role of photographer, friend, support, and first aider. “So there were several times I really had to act quickly. Of course I always had my cameras. I sometimes could quickly take pictures – as I said I was very very aware of why I was there – but then some moments I could not do anything but to intervene as I only have two hands.”

Being seen

As with most documentary photography projects, Ibasyo’s publication process was full of obstacles. Despite praise, publishers were reluctant to publish the project fearing it wouldn’t be profitable. In an attempt to get around the problem, Okahara took part in a publishing competition, but came second. Faced with the impossibility to get his book published traditionally, he contemplated self-publishing, but realized it wasn’t publication per se that was important, but rather to share his project and make the girls that worked with him seen. They had explained to him they wanted to see how others were seeing them.

Okahara crafted books for each of them, and sent them all over the world for people to read, and fill blank pages with comments to the girls. This added an extra layer of depth to the project, which eventually managed to be published. The book received positive reviews. “I have different responses from people who have different backgrounds. Most people gave me a very positive response, like people who self-harm, as well as the family members. Some psychiatrists and counselors also gave me a good response as the book really documents the everyday life of people who self-harm. In the book, I also wrote a long text, unfortunately it’s all in Japanese, which is basically about the time I spent with these girls I photographed. So there is so much about daily life.”

A project about life

Indeed, Ibasyo is not so much a book about self-injury, but rather a book about life through adversity. It doesn’t provide very much information about the behavior. Instead, Okahara chose to document the lives of some women who engage in it. “Some people want me to explain about it but my book was not to explain self-harm. It was a simple documentary of what happened, what they said, what we talked about while spending time together, etc, etc…”, remarks Okahara. During his presentation at the Cernuschi museum, he argued that many things happen in daily life, even if they are not “breaking news”, and that every image can be a strong image.

And a strong image doesn’t need to be graphic, in fact, most of the pictures don’t display any wounds at all. “There are several images that are very hard to look at, but out of many pictures they are not so many. This is because while I was taking pictures, I was focusing on whatever happens in life. While we walk, eat, have fun, chat, sometimes playing video games together. So I am hoping the pictures I selected bring the daily life of those girls who allowed me to be a part of their lives, even if it was a short moment of their life.”

Despite the book being far from gratuitously graphic nor sensational, some people criticized the project. “I also had some negative responses, especially from some people who are doing research of self-harm and who actually self-harm saying I am just giving an emotional porn,” regrets Okahara. “One of the reasons is that the girls I photographed, most of them had overcome self-harm when I published the book. This is because it took me 15 years to publish this book and the girls became ok. Some criticized this as fiction as they didn’t like the fact the girls became ok. I wasn’t really aiming for that but as it took me 15 years to make a book… and it was long enough for the girls I photographed to overcome. It was by chance.”

It’s highly questionable that some critics could be unsatisfied by the recovery of the women featured in Ibasyo. In his presentation last month, Okahara said he was still friends with them, and that they are all now fine. This sends a strong message of hope, and shows that while mental health issues are difficult, regardless of where they stem from, they may not always last.

For more information about Kosuke Okahara’s work, you can visit his website where you can buy his book Ibasyo.