WARNING: This article contains graphic photos.

First published on August 31 2024. Last edit on October 10 2025.

We arrived at Guardia Sanframondi early in the morning on Saturday 24th. It’s a medieval hill town in the province of Benevento, Italy. The only way to reach it by public transportation from Naples, the closest large city, is through a two-hour long bus journey programmed only twice a day. We were coming for the 2024 edition of Riti Settennali, a penitential festival in honor of the Madonna dell’Assunta, our lady of the Assumption. The festival takes place only once every seven years, starting on the monday following August 15th, and spans an entire week. We were dropped off the bus on the main street, and while at first the town appeared calm, we could feel people were getting ready, and were starting to meet with their friends and family. The medics from the Italian Red Cross were also setting up medical tents.

The event had already started several days prior and the processions from each district, named rione, were over. From monday to friday, the four districts which make up the town (Croce, Portella, Fontanella and Piazza) had paraded two different processions, one of penitence, called di penitenza, and one of communion, di comunione, with banners representing their district1.

On Saturday the procession of the clergy took place, which we witnessed. The clergy and the spectators converged on the square in front of the Basilica dell’Assunta. This is where the statue of the Madonna dell’Assunta is kept in a display case. After the procession of the clergy, the case was opened and the crowd gathered to bear witness, even after the sun set. During both the day and the night, the square was buzzing with a religious fervor. The event was to reach its peak on Sunday, for the processione generale.

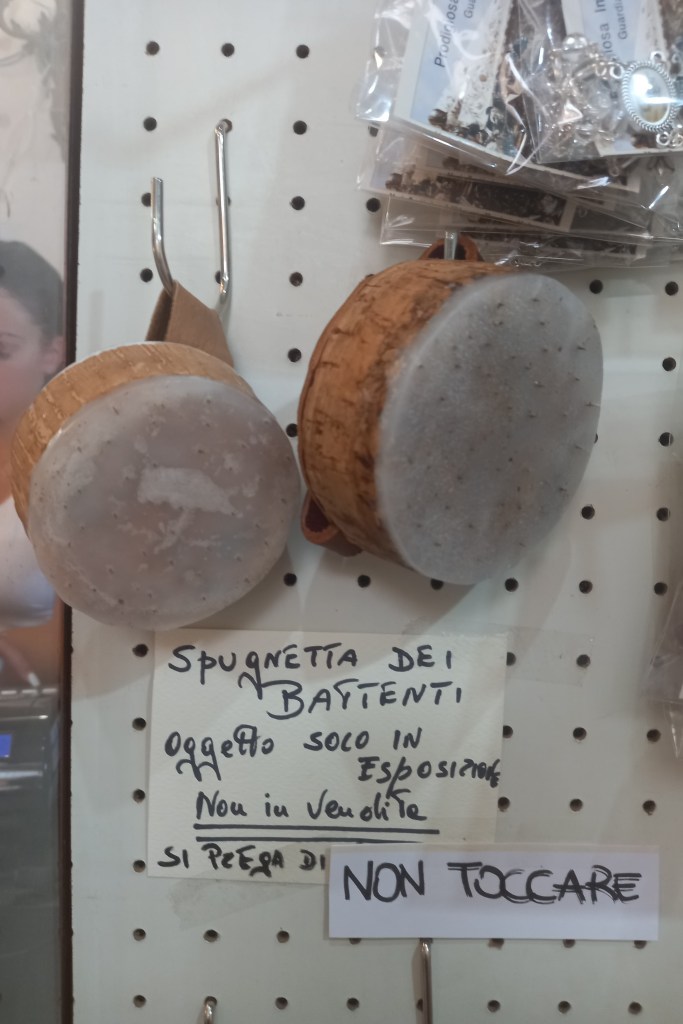

But before calling it a day we headed to the souvenir shop. Among some materials about the event, we picked up a discipline. It’s different from the one used by flagellant, likely because it’s supposed to be decorative and not actually used. How ironic that an event which claims to be faithful and traditional trivializes one of its biggest symbols of piety.

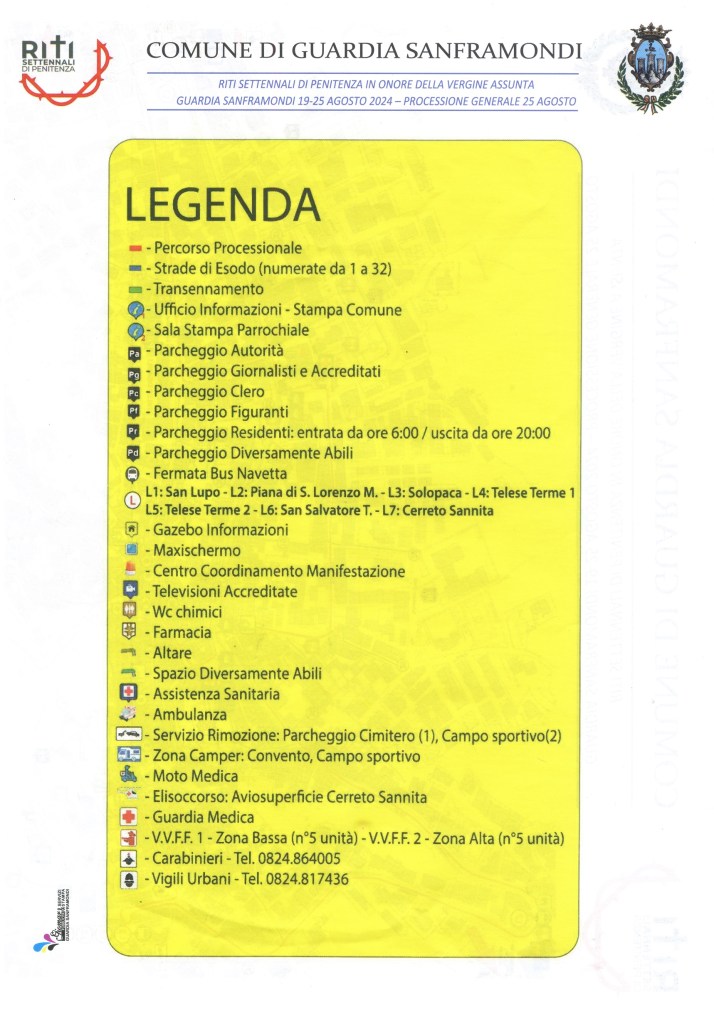

That evening we picked up my press kit, full of documentation about the event and a press badge. Back in the rental house, we rested, looking forward to the processione generale taking place the day after.

The processione generale is definitely the most popular and controversial part of Riti. It attracts believers, photographers, journalists, and curious people who are keen to witness the uncanny acts of public corporal penance that take part during it, some of the last that still exist in Europe. It isn’t surprising, given how rare mortification of the flesh has become, and our difficulty to understand it in a modern world where physical pain and religion are less present in our daily lives. Though it is important to keep in mind that to the penitents, this is not a form of masochism. They claim they don’t enjoy the pain per se, but rather see it as a way to reflect on their sins, repent, and get closer to God. Suffering without an internal spiritual reflection holds no value in Christianity2.

On Sunday morning, flagellants clad in a white robe and hood converged toward the Basilica dell’assunta. While the metal whip they used, called a discipline, only drew blood in a few rare cases, it appeared to be painful given its weight and the repetition of the act. Their discipline made a very distinctive metallic clicking sound which accompanied them through their march. The flagellants would later become battenti: they would beat their chest with a spugna, a cork circle protected by a layer of wax on which pins have been attached. The instruments of penance are crafted by hand in the period before riti, and only in the necessary quantity for the penitents3.

After the penitents and the public finished gathering in the square of the basilica dell’Assunta, a mass was held, and then the processione generale started, beginning with the shout “Fratelli, in nome della Vergine Assunta, con forza e coraggio, battetevi!”. This call signalled to the battenti to start their mortification, and so they started marching out of the square, beating their chest with the spugna.

We were looking for the procession, but it would be fairer to say the procession found us. We were passing by a narrow street when we were ambushed by a crowd of people, and a never-ending flow of participants marching toward us. It was impossible to go through the procession, so we decided to stay there and watch it. The whole community of Guardia Sanframondi contributed to Riti and almost every local seemed to play a role in it, whether as a participant or a spectator. Many were wearing some symbolical signs of penance, such as a crown of thorns or a braided rope crossed on their chest.

Sunday’s procession started with misteri: living frames about historical or religious figures, recreated by actors. Each misteri was introduced by a sign that indicated the theme, carried by a child. It was clear that having to stay in a frozen position was very tedious for the actors, and several broke out of character to rest their limbs when the procession was backed up for a few moments.

After the misteri, specifically the one representing “San Girolamo penitente”, came the battenti, arranged in two rows, each with a side of their shirt now opened. Some had a square-shaped pocket which could be opened, though most simply unbuttoned their shirts. Ironically this sometimes wasn’t enough, requiring a collaboratore battenti to fold the collar aside to create more room. Others also used pins to hem their hood, and some made a knot to keep it tight.

During the whole procession, a woman chanted the Litany of Loreto, to whom the men replied back, “Ora pro nobis”, as they repeatedly pierced the exposed part of their chest, with the spugna with one hand while gripping a crucifix in the other. Their disciplines, afixed to their waist, made a distinctive clicking sound as they walked.

Despite the robes and the face cover, tiny details reveal a part of a battenti’s identity. Although most were wearing sneakers for the lengthy march, some were clearly trendy. Others had tattoos or were wearing jeans alongside, suggesting they were young. We didn’t expect such a contrast between the formality of this ancient religious tradition, and the casualness of some younger participants. A few women also took part, though unlike the men they were not topless under the open robe but were wearing a tank top or a bandeau bra to wrap their breasts. The participation of women in corporal penance processions used to be prohibited, but their presence has become increasingly tolerated overtime4. Nowadays a few can be spotted, though they still try to obscure their gender. Battenti were also diverse in the level of mortification they would decide to endure. A few would beat both sides of their chest, but most would focus only on one, usually the left side – probably given the majority of people are right handed. Some harmed themselves much more than the rest, causing a large amount of blood to run down their chest and soak into their robe: battenti can chose between spugne with different lengths of pins, the longer ones leading to more harm5.

Indeed, unlike that of flagellants, the procession of the battenti drew blood. Still stuck in that tiny street, the act spattered tiny droplets of blood on our arms, clothes, and cameras. Collaboratore battenti wore thin white coats and were charged with pouring white wine onto the spugna to disinfect them and prevent infections. The word “Vino” flowed back and forth, a suggestion from the assistants, and a request from the penitents. Some assistants even had pouches attached to their waist, to carry as many bottles as possible before reloading. To control the flow of the wine, some used their thumb to partially block the neck of the bottle, while others pre-pierced the caps of bottles. They had to exchange these custom caps quickly to avoid a hold-up, and were constantly jogging back and forth to reload. White wine gradually covered the ground, leaving its scent hanging in the air long after the battenti had passed.

A few flagellants closed the penitents’ procession, and more misteri paraded, including little boys in black robes but without head coverings. They carried smaller disciplines, whipping their backs as they walked. Whether it was pretense, or rather education to follow the path of grown-up repentents, we couldn’t tell. The procession was long, and went through the entire town. In the main street, barriers were separating the crowd of spectators from the participants of misteri and the penitents. The battenti met the statue of the Madonna dell’Assunta at one point in the procession and kneeled in front of it. Unfortunately we were unable to witness this moment.

When the procession finished parading through the street where we were, it became silent and deserted. Empty wine bottles were dropped all across the town, tracing back the path followed by the battenti. Only the smell of wine remained, and blood spatter all along the walls. An Italian photographer saw us take photographs of the wall. “Oh… Il sangue!”, she exclaimed as she noticed the tiny red stains. Interested, she documented the aftermath of the procession as well.

Late in the afternoon, we isolated from the crowd and climbed further up the town. Even from far away, we could still hear the chants, resonating throughout the streets and the hill. Many of the houses and apartments lining the narrow alleys were abandoned and deteriorating. Based on pictures on the wall and papers in drawers, one belonged to a young man, who probably left Guardia for a more populated place nearby. With so many building falling into ruins, and the population aging and declining since the 1950s6, we couldn’t help but discuss the future of Riti Settennali. With the recent advent of the internet and social media, the event is being introduced to a larger audience worldwide, compelling many tourists come to see it. And yet, will there be any young locals left keen to perpetuate the tradition in a few decades? As often with traditions, there is a risk of it either disappearing or selling its authenticity for profit.

We’ve only spent three days in Guardia, but it felt as if the days were taken out of the traditional time frame. From morning to evening, we could hear religious chants resonating through the town, and perhaps even in the hills surrounding us. Riti wasn’t a comfortable experience, but it was probably the only way to truly experience it. We had little sleep, woke up early and went to sleep late, and so did the entire town due to the night masses and frequent early gatherings at the square near the basilica dell’Assunta. The heat, the constant stairs to climb, the smell of wine, the blood splatters on us, the lengthy processions, the sounds of bells, choirs and of the never-ending repetitive litanies, all these elements made Riti an uneasy sensory experience, but no doubt the exhaustion and the pain was worse for the participants. The few events we’ve witnessed during the Riti Settennali will stick with us for a long time, but will never feel as real as when they unfolded around us.

References

[1] Lombardi, G., & Lombardi, O. (n.d.). Riti Settennali. Ritisettennali di Guardia Sanframondi. https://www.ritisettennali.org/

[2] Pigna, N. (2024). La penitenza: come intenderla nel mondo contemporaneo. Santurio dell’Assunta, LXIX(5/6), 6-8.

[3] Ufficio Stampa Riti 2024. (2024). Email August 22 2024 [Reply to an email].

[4] La penitenza femminile. (n.d.). In Il corpo penitente nei Riti Settennali di Guardia Sanframondi (pp. 41-44). https://www.ritisettennali.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Il-corpo-penitente-nei-Riti-Settennali-di-Guardia-Sanframondi.pdf

[5] Anteprima24 Video. (2024). Guardia Sanframondi, alla scoperta delle spugnette usate per i Riti Settennali. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Al_xTn55uj0

[6] Numero abitanti a Guardia Sanframondi. (n.d.). Comuni Italiani. https://www.comuni-italiani.it/062/037/statistiche/popolazione.html