When we think of self-harm, we tend to subconsciously associate it with a specific gender and perhaps for most people, the stereotypical “self-harmer” is a teenage girl who cuts herself. But self-harm is a complex behavior which cannot easily be simplified without taking the risk of being misunderstood. In this article we will explore the differences between both genders in self-injury.

Prevalence

The rate of self-harm per gender is subject to dispute within academia. Self-harm is often a private behavior, meaning that most people who self-harm go unnoticed. People who are known to self-harm, either by seeking help or participating in studies, might not represent the global population as stigma could deter other groups from disclosing the behavior. Similarly, cases observed by emergency services might only include the most serious ones.

Several surveys showed that self-injury is more common in women than men, with females making up 60% and men 40% of people who self-injure1, 2. However, results are inconsistent and some studies found no difference in self-injury ratio between genders.

We can explain this difference in results by the difference of populations studied. Researches which find a higher prevalence of self-harm among females tend to focus on teenagers, while those which find no gender difference tend to focus on young adults, suggesting the rates vary across age groups3.

Indeed, a study on self-injury and self-poisoning regardless of suicidal intent found a much higher rate in girls than boys (aged 12-13). However, the discrepancy between male and women ratios of self-harm then gradually decreased in older populations. In people aged 50 and over, the ratio was reversed and self-harm became more prevalent in men than women. While it is important to keep in mind that this study made no distinction between non-suicidal self-injury and self-harm with suicidal intentions, it suggests there are differences between male and female self-injury2.

Differences between genders

Indeed, male and female self-injury differs in several factors. Girls start engaging in self-injury at a younger age than boys1. Such a difference could be explained, among other reasons, by a greater level of distress in young girls4 and an earlier onset of puberty and depression in girls than boys1, 2.

Women who self-harm also tend to show an increased risk of comorbidity with eating disorders than their male counterparts5, 6. Men, on the other hand, report self-injuring more often under the influence of substances7, 8. Understanding such risks suggests that gender-targeted prevention regarding eating disorders and substance abuse could be helpful to those who self-injure.

Another difference can be found in tendencies regarding locations of injuries between genders. Men tend to injure their chest whereas women injure their arms and legs more often3, 7.

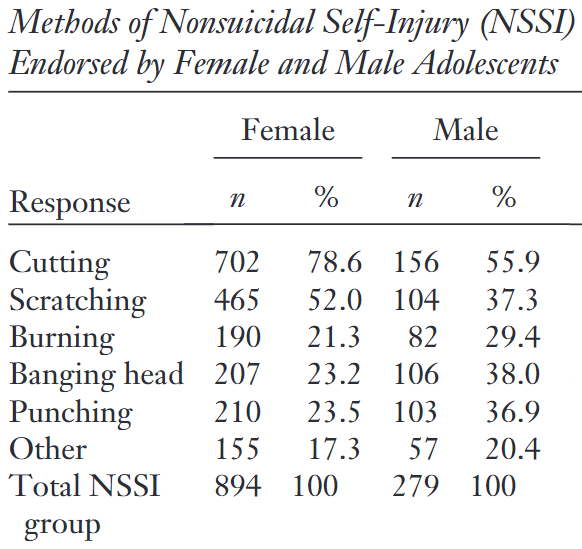

The methods used for self-injury differ as well. Women are more likely to cut or scratch themselves whereas males tend to punch themselves or an object, bang their head, or burn themselves1, 3, 8. Again however, results must be interpreted with caution as several studies found cutting to be the second most cited method among males, behind hitting-type behaviors3.

Methods more predominantly used by men such as kicking or hitting objects can be misunderstood as outward aggressivity as opposed to self-injury8, 9. This can have serious consequences as not including specific methods in the definition of self-harm or surveys can render invisible a large population who yet needs help. It can also reinforce stigma when someone does not feel they fit the norm1, 3.

Little is known for now regarding the functions of self-injury for each gender, but we can assume that there are differences as well5. It appears that men engage in self-injury out of anger more than women8 although more research is required regarding this aspect.

Conclusion

Up until the 21st century, due to the belief that self-injury was a female behavior, most studies about non-suicidal self-injury were conducted on samples composed mainly or exclusively of women1, 9. Failure to question and go beyond preconceptions can have harmful consequences as conclusions drawn on female self-harm may not be generalized on male self-harm1. This can prevent men from accessing treatment if their mental health issues are not recognized, due to not fitting the stereotypical forms of self-injury. As women are more prone to talk and seek treatment about their self-injury, perhaps due to the stigma attached to male mental health issues7, 9, it is essential to learn to identify signs in men.

Another problematic aspect is that most research on self-harm applies a binary understanding of gender, which can exclude people who identify as neither strictly male nor strictly female. Yet, we know that members of the LGBT+ community are more at risk of self-injury7.

A parallel theory on self-injury and gender supports the idea that it is not gender per se that has an impact on self-harm, but abuse, which tends to impact women more than men10. This will be the focus of another article.

References

[1] Andover, M. S., Primack, J. M., Gibb, B. E., & Pepper, C. M. (2010). An Examination of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Men: Do Men Differ From Women in Basic NSSI Characteristics? Archives of Suicide Research, 14(1), 79-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110903479086

[2] Hawton, K., & Harriss, L. (2008). The Changing Gender Ratio in Occurrence of Deliberate Self-Harm Across the Lifecycle. Crisis, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.29.1.4

[3] Sornberger, M. J., Heath, N. L., Toste, J. R., & McLouth, R. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury and gender: patterns of prevalence, methods, and locations among adolescents. Suicide & life-threatening behavior, 42(3), 266-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278x.2012.0088.x

[4] Wilkinson, P. O., Qiu, T., Jesmont, C., Neufeld, S. A. S., Kaur, S. P., Jones, P. B., & Goodyer, I. M. (2022). Age and gender effects on non-suicidal self-injury, and their interplay with psychological distress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 240-245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.021

[5] Bakken, N. W., & Gunter, W. D. (2012). Self-cutting and suicidal ideation among adolescents: Gender differences in the causes and correlates of self-injury. Deviant Behavior, 33(5), 339–356. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/01639625.2011.584054

[6] Warne, N., Heron, J., Mars, B., Moran, P., Stewart, A., Munafò, M., Biddle, L., Skinner, A., Gunnell, D., & Bould, H. (2021). Comorbidity of self-harm and disordered eating in young people: Evidence from a UK population-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 386-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.053

[7] Lewis, S. P., & Hasking, P. A. (2023). Understanding Self-Injury: A Person-Centered Approach. Oxford University Press.

[8] Whitlock, J., Muehlenkamp, J., Purington, A., Eckenrode, J., Barreira, P., Abrams, G. B., Marchell, T., Kress, V., Girard, K., Chin, C., & Knox, K. (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in a college population: general trends and sex differences. Journal of American college health, 59(8), 691-698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.529626

[9] Victor, S. E., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Hayes, N. A., Lengel, G. J., Styer, D. M., & Washburn, J. J. (2018). Characterizing gender differences in nonsuicidal self-injury: Evidence from a large clinical sample of adolescents and adults. Compr Psychiatry, 82, 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.comppsych.2018.01.009

[10] Gómez, J. M., Becker-Blease, K., & Freyd, J. J. (2015). A brief report on predicting self-harm: Is it gender or abuse that matters? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(2), 203-214. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/10926771.2015.1002651