The following article deals with sensitive topics which may be distressing to some readers.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the intentional damage of one’s body without suicidal intent and for reasons that are not socially or culturally accepted. Several methods are used, such as cutting, burning, hitting or scratching. Depending on the method used and the severity of the injury, the behavior can draw blood. From 40% to 50% of those who engage in self-injury attach importance to the sight of blood during self-injury1, 2, 3 and research has found that those who see the presence of blood as important tend to engage in the behavior more frequently1, 2. We might therefore wonder why blood is important to them and what value they attach to it.

Symbolism

Blood has been frequently described as carrying aesthetic value4. Throughout history, it has also been considered a means to cure from illness5, through blood-letting for instance6. While the medical practice has since become obsolete, some symbolic connotations of blood remain. For instance, in her book A Bright Red Scream, Marilee Strong recounts the case of a man who self-injures and who cuts “primarily for the blood”. He explained that the process of bleeding made him feel purified, as if negativity or impurity left his body with the blood. Blood can also represent life, and its sight can therefore be considered a visual proof to some individuals that they are alive, along with the feeling of its warmth7.

Functions and mechanism

While the sight of blood during self-injury has multiple functions, individuals who self-injure commonly describe it as comforting and report that it serves to relieve tension and calm down1, 2, 3.

This potentially soothing effect of blood could be explained by its effect on the body. Seeing blood first produces an acceleration of the heart rate, possibly in order to enable the body to take defensive action when confronted to a threat1, 8. This initial acceleration is then followed by a deceleration of the heart rate that could occur once the body realizes the absence of threat1 or in the case of a fear-induced freeze (fear-induced bradycardia), as has been observed in some animals8. These two mechanisms could explain the calmness many people report feeling after self-injury.

Conclusion

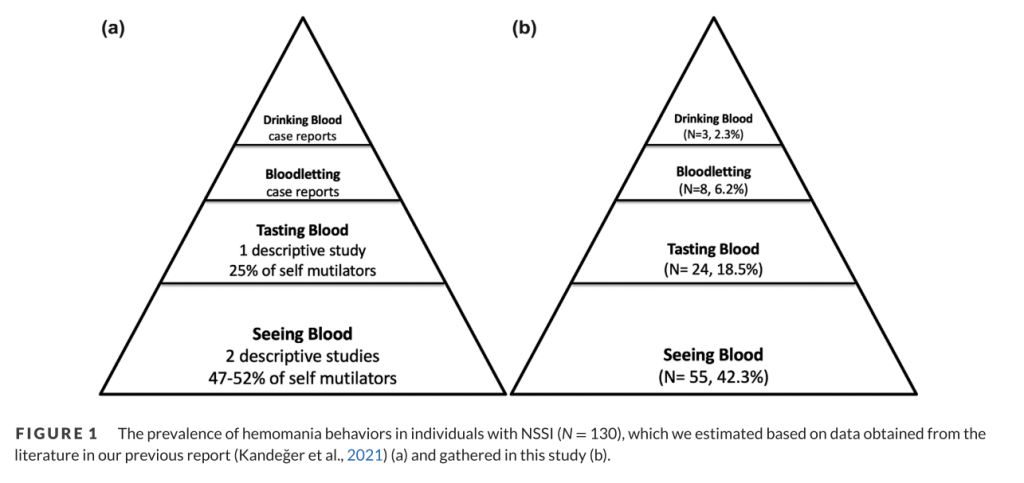

Blood is rarely addressed in research, despite the greater vulnerability and high prevalence of individuals who attach importance to it. So far, the few papers that investigated its role mainly focused on sight. Yet, in a survey focusing on females who engaged in self-injury2, 25% – one out of four respondents – reported liking to taste their blood. This finding is corroborated by a recent study on 130 participants with NSSI that found that 18.5% report tasting their blood (see figure below).

Such results reveal some individuals do not only look at their blood but aslo interact with it, an aspect that has been excluded in most research about blood9. It can be difficult to understand why someone would engage with their blood, and this lack of understanding can lead to shock and inability to help. Some people might exaggerate the severity of the behavior while others might refute it as a deviant act which does not have any psychological causes. Therefore, better understanding the value associated with blood, as well as the mechanisms involved, could help reduce the stigma and adapt treatment and therapy to this population.

References

[1] Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2010). The Role of seeing blood in non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(4), 466-473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20661

[2] Favazza, A. F., & Conterio, K. (1989). Female habitual self mutilators. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 79(3), 283-289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10259.x

[3] Kandeger, A., Uygur, O. F., Ataslar, E. Y., Cinar, F., & Selvi, Y. (2024). A pilot study examining hemomania behaviors in psychiatry outpatients engaged with nonsuicidal self-injury. Brain and Behavior, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.3475

[4] Franzén, A. G., & Gottzén, L. (2011). The beauty of blood? Self-injury and ambivalence in an Internet community. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(3), 279-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.533755

[5] Favazza, A. R. (1996). Bodies Under Siege: Self-mutilation and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry. Johns Hopkins University Press.

[6] Chaney, S. (2017). Psyche on the Skin: A History of Self-Harm. Reaktion Books.

[7] Strong, M. (2005). A Bright Red Scream: Self-mutilation and the Language of Pain. Virago.

[8] Naoum, J., Reitz, S., Krause-Utz, A., Kleindienst, N., Willis, F., Kuniss, S., Baumgärtner, U., Mancke, F., Treede, R.-D., & Schmahl, C. (2016). The role of seeing blood in non-suicidal self-injury in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 246, 676-682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.066

[9] Mohler, S. (2022). ‘Bleeding-in-the-World’: A Qualitative Study of Self-Cutting and Blood [Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University]. https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/2088/