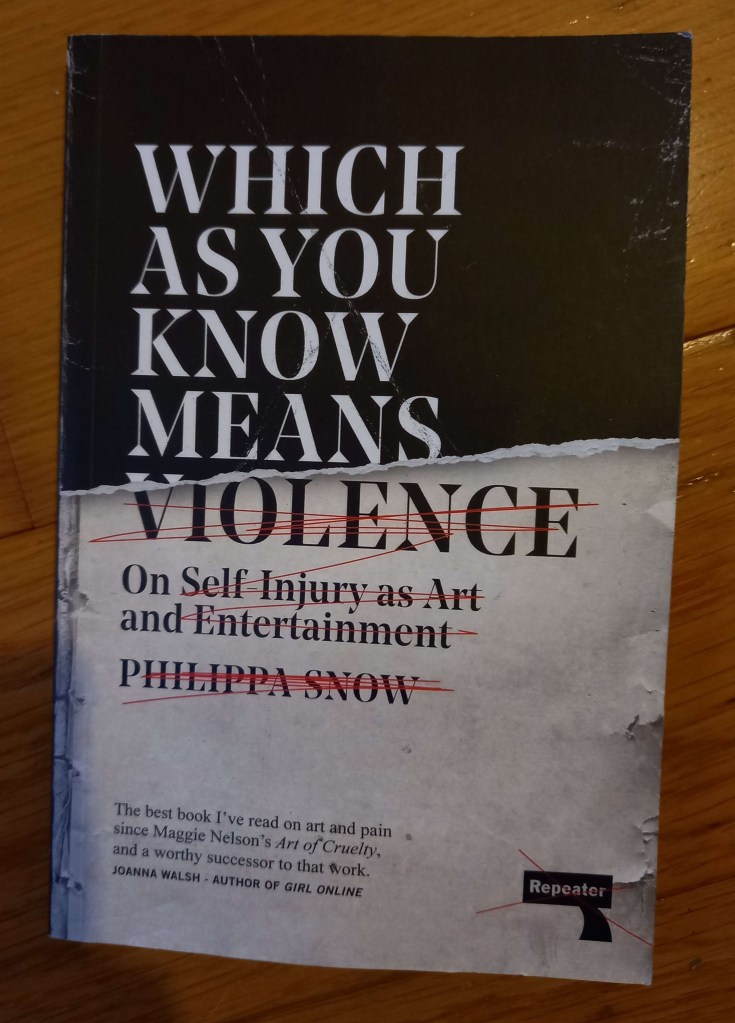

Which as You Know Means Violence: On Self-Injury as Art and Entertainment is an essay written by Philippa Snow and published in 2022 by Repeater. It is a reflection about self-injury in art and entertainment, stemming from an answerphone message left by writer and journalist Hunter S. Thompson to Jackass’ Johnny Knoxville: “I will be looking to have some fun, which as you know usually means violence.” Why is violence fun to some artists and entertainers, and what does it mean to them, are questions that Philippa Snow aims at answering.

Snow first goes to show how some artists and entertainers might be drawn to using self-injury in their work to heal the traumas of a troubled childhood or of the geopolitical and social context of the times, such as war for instance. To illustrate her point, she uses the examples of Jackass’ Johnny Knoxville and artists Chris Burden, Gina Pane, Ron Athey and Marina Abramovic. Gina Pane for instance, in her work Action Escalade non-anesthésiée, used self-mutilation to raise awareness to the suffering inflicted by war in Vietnam. As for Ron Athey, who grew up in an dysfunctional family, he used self-harm in his teens both as a way to feel alive and to dissociate from guilt, and later kept the practice in his art to leave his mark after getting infected by HIV. Ron Athey’s case is also the opportunity for Philippa Snow to comment about how most self-mutilation performances are done by white artists, which seemed to be rather off-topic in this chapter and too superficially treated to be thought-provoking. She concludes chapter 1 by pointing out that this attempt at cheating death by using self-mutilation in art is mainly done in youth and tends to decrease with age, perhaps as the perspective of death gradually becomes more real as we grow old, an interesting point as it suggests that maybe while those artists are born different, we all grow old the same.

In Chapter 2, Snow reflects about female use of self-injury in art and entertainment, using the example of Rad Girls, a female alternative to Jackass that challenges the stereotypes of women being calm and virtuous, and Marina Abramovic, who in some of her work with ex-partner Ulay, remained relatively conformist to heterosexual and gender norms. According to Snow, female self-injury in art can mainly be seen through its relation with men: while in the real world women are hurt and suffer because of men, in art they inflict the pain themselves, a way to both point out and break free from woman’s fate of inherent suffering. It is therefore a paradoxical mix of submission and independence: if they cannot escape the suffering, they can at least be the ones delivering it upon themselves. Snow then adds that if violence against women has been normalized, female self-violence remains shocking, particularly as it damages what is considered their value: their beauty and fertility. And yet, far from danger being only a lack of control, women can enjoy the thrill of risk and violence as well, as in the case of Paige Ginn, a young woman who filmed herself faking accidental falls in public. Snow also mentions Nina Arsenault, a trans artist who underwent numerous plastic surgery, to show how suffering can be a constructive tool to shape one’s identity. Arsenault plays with the stereotypical features of femininity, just like the Jackass team plays with the stereotypical features of masculinity. She concludes by stating that “when men do hurt themselves, it tends to be in order to create a show of strength, and when women do, it tends to be in order to be either expressing resistance to oppression, or embodying it physically in such a way as to unnerve or fuck with those watching them”. Such a claim is questionable: women are not only defined by the oppression they are victims of, and, just like men, they suffer from a great diversity of issues, some indeed specific to their gender, such as sexism, but also many topics universal to all human beings. It is unfortunate that Philippa Snow reduces women’s self-injury to their nature as women. In art, for example, Gine Pane’s Action Escalade non-anesthésiée, mentioned in the first chapter of the essay, is a protest against war in Vietnam, and therefore is not that different to Scorcese’s The Big Shave. While Philippa Snow makes several interesting points, it seems as if she can not escape the scope of gender studies, which while at first offers a fresh perspective to the topics of self-injury and entertainment, quickly becomes limiting.

The key idea in chapter 3 is unclear, but Snow focuses more on self-injury in cinema, starting with the example of director Harmony Korine and an abandoned film project titled Fight Harm, in which Korine himself was filmed fighting with people bigger than him, and getting hurt. According to the director, who is also a great fan of Buster Keaton, Fight Harm was an attempt at creating the ultimate slapstick comedy, a movie genre that relies on falls and accidents to make the audience laugh and be relieved they are not the ones injured. Keaton himself was no stranger to risk-taking in cinema, as testified by the notorious scene from his 1928 movie Steamboat Bill Jr, in which a two-ton frontage of a house falls down around him, a stunt that would have been lethal had the actor moved just a few centimeters. Snow then wonders what distinguishes between an artist and an entertainer, and suggests these two fields are not that distinct, especially when self-injury is involved and is a proof of commitment to make people laugh, feel and think. However, this drive to put one’s life at stake out of full commitment can also stem from a darker place. Buster Keaton for instance, was alcoholic and his marriage was falling apart when he performed the deadly stunt, and “crew members excused themselves before the stunt to avoid witnessing a suicide”. Unfortunately, the psychological aspect behind self-injury is left unanalyzed by the author.

Chapter 4 deals with the topic of death, first focusing on its relationship with sexuality, as highlighted by Bob Flanagan’s life and work which mixed sadomasochism with illness. Flanagan suffered from cystic fibrosis his entire life and was told he would die in his early 20s but ended up living 20 more years than announced. As he could not eliminate the pain, he made it part of his work and sexuality, a use of self-injury that could be described as therapeutic in that it was bringing him relief which he attributes his unusual longevity to. Nevertheless, as he was dying and pain reached a new level of intensity, the idea of suffering stopped being arousing to him, and became instead irritating. Snow notes that while Flanagan’s life-long suffering, his last moments, and the photograph of his corpse were documented and published, the actual moment of his death was not, as if too intimate and more taboo than self-injury and sexuality, a sacrifice that no artist has yet been willing to make. Death videos however are sadly not uncommon online, and even starts infiltrating the mainstream, as testified by Logan Paul’s video showing the corpse of a man who committed suicide in the Aokigahara forest in Japan. This point is interesting but does not seem relevant when talking about self-injury. Snow then refocuses on that topic and transitions from Paul’s Youtube video to the accidental death of a young man shot dead as he was performing a stunt for another Youtube video with his girlfriend. He was not naive about the possible lethality of the stunt, but was driven by his appeal for money.

As can be seen by the numerous diversions in the essay, the book is rather unstructured, similar to an ongoing thought, with Snow commenting upon whatever artwork, TV show, novel or Youtube video that comes to her mind. As the author explains in the introduction, this book was not meant to be an academic text but rather a reflection upon topics she was curious about: self-injury in art and entertainment and its connection with gender and power. Intersectionality takes a large part of the essay, but the topic of the book was mislabeled. The reader might have expected a more universal, perhaps more psychological analysis of self-injury in art and entertainment. Once the premise is understood, the book is successful in touching upon such matters but self-injury is unfortunately seen only through this aspect, which is extremely reducing. For what seemed to be only a digression at first quickly became the very topic of the essay, eclipsing self-injury.

Snow, P. (2022). Which as You Know Means Violence: On Self-Injury as Art and Entertainment. Repeater.