Warning: this article contains graphic photographs.

During the month of Muharram, Shiite Muslims commemorate the death of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Mohammad, who was killed with members of his family by the army of Yazid (one of the first caliphs of the Umayyad Caliphate) during the battle of Karbala, 680 AD 1. Hussain refused to submit to Yazid, despite his army being drastically smaller, and is therefore seen as a model of resistance against injustice and tyranny. The mourning celebrations are composed of four rites:

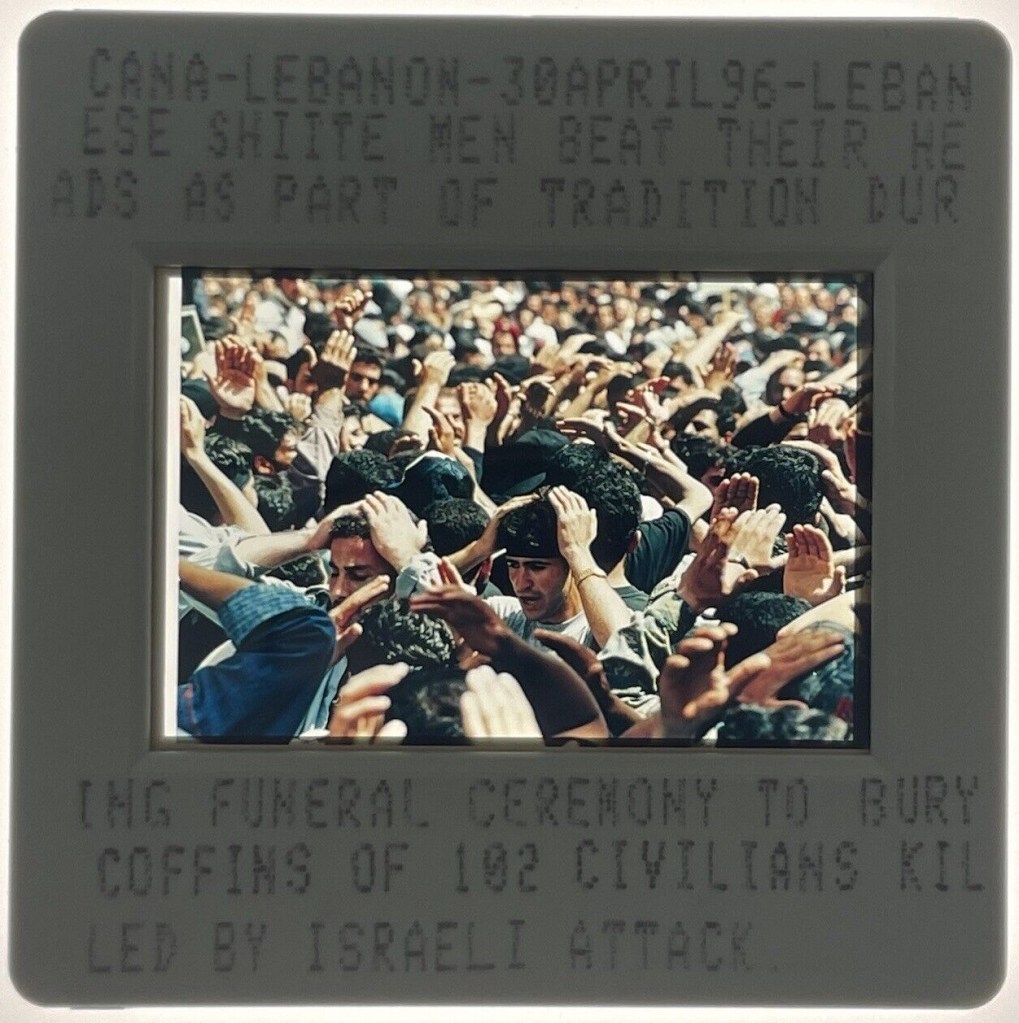

- Lamentations consist of the narration of the battle of Karbala while the audience weeps. Men beat their chest in rhythm with the telling or singing. The chest-beating is known as “sineh‑zani” 1, 2, 3.

- Public processions are organized based on neighborhoods, friendship, or political opinions, during which men sometimes take part in self-flagellation.

- Plays are performed in some countries, especially in Iran, depicting the events that are commemorated 2.

- Finally, participants visit a holy place, such as shrines or, when they are able to, make a pilgrimate to Karbala 2.

During these mourning days, Shia Muslims abstain from sexual relationships and often wear black clothes 2. Ashura, the 10th day of the month of Muharram, marks the climax of the celebrations. On this day, male Shiites observe a mourning rite known as “matam”, which consists of striking oneself, either with the hand, or with instruments in which case it is known as “tatbir”. The latter term varies depending on the region and the method used to inflict injury, the table below summarizes some of these variations 3, 4, 5, 6.

| Term | Region, language | Definition |

| latm | Arabic | Chest-beating with the hand |

| matam | Persian | Act of mourning with chest beating or self-inflicted injury |

| qama-zani / ghameh-zani / qameh-zani | Persian | Cutting of the head |

| sineh-zani | Persian | Chest-beating with the hand |

| tatbir | Arabic | Self-inflicting injury during ashura |

| zanjir-zani / shamshir-zani / zanzeer | Persian | Flagellation of the back with sharp instruments |

For the sake of clarity, we will use the term “tatbir” to refer to any form of self-inflicted injury during ashura which draws blood. Tatbir involves self-whipping with sharp objects attached to chains, and the cutting of the forehead with a blade. In Syria and Lebanon, the chains used for flagellation are light and do not have spikes nor blades, thus they do not cause any injury 2, 5. Younger men usually perform the most violent forms of self-flagellation 5. The rite is performed out of love for Hussain3, and to repent for having given him up, identifying with the villagers who did not save the imam in Karbala 2, 6. Many Shia muslims also believe that tears shed for Hussain will bring them rewards and redemption from Allah 5.

Blood-drawing flagellation for Ashura appeared in Iran in the sixteenth-century but may have been derived from pre-Islamic funeral practices. Its spread from Iran to other countries have contributed to a regional diversity of practices 5. It now takes place primarily in Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, and Oman, and to a lesser extent in Afghanistan, Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria. It has also begun to appear in Europe 7.

A ritual that reaffirms social ties and identity

The mourning ritual during Muharram is seen by some Shiites as a unifying tradition that defines their community. Indeed, while some Sunnis also mourn Hussain’s death, only Shia muslims perform matam and beat their chest or flagellate – the rite being often criticized by Sunnis – which creates a sense of identity. Therefore, Ashura is the opportunity for all the Shia community to be united in mourning 6, 8, 9. During the ritual, refreshing drinks and food are often distributed to remember the thirst which Hussain suffered from 1. Each flagellant procession, known as dasteh or hey’at, has a specific identity, with its own name, flag, rhythm, flagellation method and therefore represents the community it comes from 1. Ruffle 3 argues matam can be “an efficacious tool for spiritual growth and for reaffirming family and social ties”. It is also a rite of passage for young boys, a “kind of masculine endurance test” as David Pinault 6 calls it, and therefore codifies gender roles. Boys learn how to perform tatbir by observing men, and replicate it, gently and timidly at first, and with more strength as they grow up, gain assurance and learn to empathize with Hussain’s suffering 2, 3, 9. Women also have a codified role, as is developed in this article.

In Lebanon, till the 1970s, tatbir was mainly performed by lower-class men, even sometimes by “bad boys”, but since then, participants became more diverse and the rite became a political means to rally the “shia masses” 2.

In Iran, as urbanization reshaped traditions, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, younger generations, who moved to bigger cities to find work, were willing to preserve and take part in the traditions of the native villages. They would film self-flagellations and consult older generations, in order to preserve local self-flagellation ways. However, they were not reluctant to modernize the rituals, for instance by introducing a new self-flagellation method which uses metal chains. This attachment to the hometown decreased as the following generations became more urbanized 1.

In the 20th century, we saw an increased occurrence 5 and visibility of bloody mourning rituals during Ashura, that can be attributed to three factors: the decrease of oppression on shiite minorities in the Middle East such as in Iraq following the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime for instance, the prohibition of mortification, and the greater coverage of such practices caused by the development of Arab satellite TV channels 2. Interestingly, Sadam Hussein banned Shia mourning rituals, from fear it could mobilize crowds. In other countries, tatbir is seen as a way to resist foreign imperialism. It reveals such rituals have a political and even revolutionary aspect 10.

The recent spotlight on those rites that used to be performed discreetly and sometimes clandestinely launched a debate surrounding the practices.

A controversial rite, even within the Shiite community

Despite its potentially unifying value, tatbir can also be divisive as not all shiites approve of it. Anti-tatbir scholars advocate for modernization of Shia practices, arguing that it is forbidden in Islam to harm oneself, that the rite is neither based on the Quran nor the hadith and is therefore an innovation, and that it gives the world a bad image of Shia muslims and Islam as a whole. As for defendants of the rite, they claim that tatbir is a tradition, a way to replicate the pain endured by Hussain and that no-real harm is caused, the practice being relatively harmless and flagellants often feeling no pain in the process. Some also classify mourning practices in a hierarchical order, deeming people who shed tears without shedding blood are childish and that those who perform bloody flagellation are closer to the pain of Hussain than those who flagellate with harmless chains. Others believe that it is more important to relate to the Imam’s emotional suffering than to his physical pain or prefer quiet prayer 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11.

In that context of debate, scholars classify the rite, ranging from forbidden to obligatory, by way of permissible, recommended, or reprehensible. Shias decide which of them they want to follow. This need to convince and attract followers lead to some scholars being reluctant to condemn tatbir 5, 9. Several clerics, however, have taken steps to ban the practice, sometimes being met with fierce opposition. Indeed, defendants of the rite see it as a way to affirm the shia identity and keep cohesion within the community 2, 5.

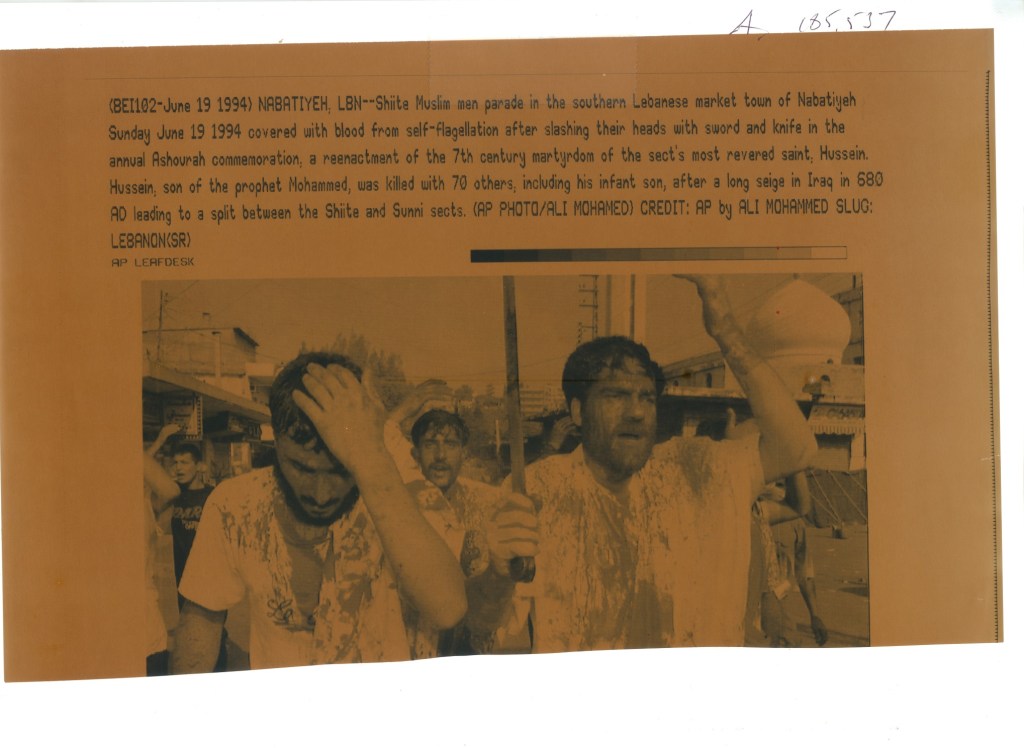

In Iran, from 1925 to 1979, rulers banned the practice in an attempt to modernize the country. In 1994, Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a fatwa to forbid tatbir, stating that the practice appears barbaric to non-Muslims and is detrimental to the image of Islam, unlike “light drumming on the head with one’s own hand” or beating of the chest which are “distinctive sign[s] of mourning” 12 [figure 1]. Accordingly, the Lebanese organization Hezbollah, which follows Khamenei’s rules, forbade its militants to perform the rite. However, while the fatwa restricts public performances, tatbir is still performed clandestinely in remote regions or outside Iran and flagellation with harmless chains remains authorized 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Other scholars restrain from forbidding the practice, provided it does not cause harm to the body. Ayatollah Muhammad al-Shiraz strongly defends tatbir, arguing that it is mentioned in the hadith, in which Zainab, Hussain’s sister, hit her head, causing it to bleed, when she saw the severed head of her brother. Al-Shiraz has many disciples in Iraq, Syria, Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia 5. Due to Khamenei’s harsh opposition to tatbir, performing bloody flagellation has also become a means to resist his leadership 9, suggesting once again that it can hold political value.

Other countries are less strict regarding tatbir. Syria tolerates the practice but does not encourage it, which, despite increasing popularity over the two last decades, has been impacted by the growing persecution of Shia muslims 2, 10. In Lebanon, where Shia are the largest religious community, processions and self-flagellation are performed publicly in the street 2.

In the past decades, shias have been encouraged to give their blood in tribute to Hussain as an alternative to bloodletting flagellation. Blood banks were created for that purpose in Lebanon, Bahrain, Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, among others. While blood giving per se is not contested as a good deed, its status as a rite is questioned by some scholars, some arguing that, similarly to tatbir, it is an innovation mentioned in neither the Quran nor the Hadith 2, 5.

In Europe, where Islam is frequently seen as violent, Shia muslims tend to avoid flagellation in any form as many consider it detrimental to the religion’s image. As a minority, they need to take into account the image their rituals give to non-muslims. Mourning processions are still organized in many European cities, but tatbir is absent and the tone is more political. For example posters are sometimes displayed reading peaceful messages to improve interreligious relationships and some charity actions for the homeless or victims of war are encouraged. In France, where Islam is facing stigma, Shia muslims celebrate indoors, away from the public eye 4, 5, 9. It is therefore interesting to focus now on how the Western world perceives tatbir.

Ashura seen by the Western world

Ashura has been written about extensively due to the violent nature of the rite of tatbir, especially by Western media seeking sensationalism and readership. Many articles online publish pictures of children with bloody faces after their parents inflicted injuries on them as part of Ashura. Such pictures are naturally shocking, especially for readers who do not grasp the broader context of the rite. However, while the internet made it easier for people to learn about foreign cultures, descriptions of mourning rituals predate by far the digital revolution.

We find European reports by travelers as early as from the 17th, but they increased in the 19th centuries 13. The ritual fascinated as much as it repulsed. Vassili Verechtchaguine for instance, described it in Le Tour du Monde, published in 1869 14. Under the appearance of truthful observation and description, the report is filled with inaccuracy, exaggeration and judgment. Tatars, the people described by Verechtchaguine, are compared to lunatics in the way they jump and shout during the first days of Muharram. Their virtue is questioned numerous times and while some depictions of acts of self-flagellation are rather reliable [figure 2], others seem taken from fantasy. The ritual is ultimately referred to as a “living painting from a fanaticism and savagery from another time”. In 1883, another French book, which lists celebrations throughout time and countries, gives a brief description of Ashura and only mentions the “weird dances” performed by people and the “fanatics” that injure themselves 15. Even when the description of the ritual is not exaggerated, as is the case in 1923’s book Un séjour aux Pays des Califes 16, the diversity of the celebrations of Ashura is rarely mentioned whereas descriptions of self-mutilations are extended. It is particularly ironic, coming from an author who, in his preface, criticized travel reports from Orient for their “regrettable shortcomings”.

However, not all Western reports of Ashura were distorted. Abbate’s account in 1888 for instance, appears to be an honest depiction of what he observed in Egypt 17. In an article from a 1905 issue of the French magazine Revue Illustrée, writer Adolphe Thalasso argues that referring to the mourning rituals of Ashura as only theatrical would be improper, stressing that all religions deserve respect and that the Shia rituals are not that different from some christian processions 18.

Conclusion

As we have seen, tatbir has an extensive media coverage due to its bloody nature. However it is important to keep in mind that the rite is only one aspect of the mourning celebrations of Imam Hussain during the month of Muharram, and that it is neither performed nor approved by all Shia muslims. Its longevity might be explained by its traditional value, along with its potential political meaning. Indeed, it enables Shiites to reaffirm their identity and oppose oppressive and foreign regimes. More generally, Hussain remains for them a model of resistance and fight for justice, guaranteeing that even if the practice of tatbir were to decrease, the core value of Ashura would be preserved.

References

[1] Vivier-Muresan, A.-S. (2020). Rites d’Achoura et affirmations communautaires. Archives de sciences sociales des religions, 189, 55-72. https://doi.org/10.4000/assr.49972

[2] Mervin, S. (2006). Les larmes et le sang des chiites : corps et pratiques rituelles lors des célébrations de ‘Âshûrâ’ (Liban, Syrie). Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerannée, 113-114, 153-166. https://doi.org/10.4000/remmm.2973

[3] Ruffle, K. G. (2015). Wounds of Devotion: Reconceiving Mātam in Shiʿi Islam. History of Religions, 55(2), 172-195. https://doi.org/10.1086/683065

[4] Astor, A., Blanco, V. A., & Cuadros, R. M. (2018, December). The politics of ‘tradition’ and the production of diasporic Shia religiosity. The Politics of Islam in Europe and North America, 32, 32-38. https://pomeps.org/the-politics-of-tradition-and-the-production-of-diasporic-shia-religiosity

[5] Flaskerud, I. (2016). Ritual Creativity and Plurality Denying Twelver Shia Blood-Letting Practices. In U. Hüsken & U. G. Simon (Eds.), The Ambivalence of Denial: Danger and Appeal of Rituals (pp. 109-134). Harrassowitz.

[6] Pinault, D. (1993). Lamentation Rituals: Shiite Justifications for Matam (Acts of Mourning and Self-mortification). In The Shiites (pp. 99-108). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-06693-0

[7] Abdalrahman, B., Walsh, B., Maimo, M., & Al-Sharif, H. (2014). A response to “infections associated with religious rituals”, by James Pellerin and Michael B. Edmond. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 22(16). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2013.11.001

[8] Pinault, D. (2001). Blood, Rationality, and Ritual in the Shia Tradition. In Horse of Karbala: Muslim Devotional Life in India (pp. 29-55). Palgrave Macmillan US.

[9] Scharbrodt, O. (2022). Contesting ritual practices in Twelver Shiism: modernism, sectarianism and the politics of self-flagellation (taṭbīr). British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2022.2057279

[10] Szanto, E. (2013). Beyond the Karbala Paradigm Rethinking Revolution and Redemption in Twelver Shi‘a Mourning Rituals. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies, 6(1), 75-91. https://doi.org/10.1353/isl.2013.0007

[11] Norton, A. R. (2005). Ritual, Blood, and Shiite Identity: Ashura in Nabatiyya, Lebanon. The Drama Review, 49(4), 140-155.

[12] Khamenei, A. (2016, October 7). Tatbir is a wrongful and fabricated tradition: Imam Khamenei. Khamenei.ir. Retrieved July 26, 2023, from https://english.khamenei.ir/news/4209/Tatbir-is-a-wrongful-and-fabricated-tradition-Imam-Khamenei

[13] Daryaee, T., & Malekzadeh, S. (2014). The Performance of Pain and Remembrance in Late Antique Iran. The Silk Road, 12(12), 57-64. https://edspace.american.edu/silkroadjournal/wp-content/uploads/sites/984/2017/09/Daryaee_SR12_2014_pp57_64PlateVI.pdf

[14] Vereschaguine, B. (1869). Voyage dans les provinces du Caucase. In Le Tour du Monde (pp. 258-273). Librairie Hachette et Cie. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k34394j

[15] Bernard, F. (1883). Les fêtes célèbres de l’antiquité, du moyen âge et des temps modernes. Librairie Hachette et Cie. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2101367/

[16] Dorville, C. (1923). Un séjour aux Pays des Califes. Barthélemy & Clèdes. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k370316t

[17] Abbate, W. (1888). Al-Achoura. Imprimerie Franco-Egyptienne. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6257543q

[18] Thalasso, A. (1905, July 1). L’Achoura. Revue Illustrée, 20(14). https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62603204