Even though people have intentionality hurt themselves “since the earliest times”1, non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) only became studied in the late 19th century. Because of this lack of research until then, it is difficult to know if NSSI as we define it nowadays existed before. Literature relates cases of people hurting themselves, but these cases are not NSSI. We define NSSI as “a self-aggressive, intentional and repetitive activity, performed without deliberate suicidal, aesthetic or sexual wish, and that is in no way socially accepted”.2 As we shall see, while religious self-harm appears at first to be purely a cultural behavior, it shows some pathological aspects as well, as can be seen in the case of self-mutilative behaviors related to christianity.

There are several mentions of self-harm in the Bible. Leviticus 19:28 and 21:5 and Deuteronomy 14:1 forbid pagan practice of mourning, that is self-cutting, tattooing and making bald patches on their heads. In 1 Kings 18:28, pagans, the Prophets of Baal “cried aloud and cut themselves after their custom with swords and lances, until the blood gushed out upon them” out of veneration for their deity.

You shall not make any cuts on your body for the dead or tattoo yourselves: I am the Lord.

Leviticus 19:28

They shall not make bald patches on their heads, nor shave off the edges of their beards, nor make any cuts on their body.

Leviticus 21:5

You are the sons of the Lord your God. You shall not cut yourselves or make any baldness on your foreheads for the dead.

Deuteronomy 14:1

And they cried aloud and cut themselves after their custom with swords and lances, until the blood gushed out upon them.

1 Kings 18:28

While those verses refer to pagan practices that were opposed by Christians, self-harm has also been practiced by many Christians for religious purposes.

Self-harm to wash away sin

There have been several cases of self-harm to wash away sin or as self-punishment for being sinful, either done by an individual or a group.

Mortification of the flesh (literally meaning “putting the flesh to death”) was done in order to wash away sins, often by self-flagellating. In some cases, the mutilations would be extremely severe. The Skoptsy, for example, were a russian sect that believed Adam and Eve had sinned by having sexual relations.1 To wash away this original sin, male members were encouraged to undergo castration and females to amputate their breasts. These mutilations were performed without anesthetics. This practice is reminiscent of Matthew 19:12:

[…] there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven’s sake. […]

Matthew 19:12

When performed by an individual, the pathological aspect of the behavior is often more obvious. There have been cases of religious people suffering from psychotic disorders, often schizophrenia, who castrated themselves, removed their eyes, or cut their hand after committing a sin, frequently of sexual nature.3 Sometimes the individual suffered from hallucination and thought the mutilation was ordered by God to redeem themselves or get closer to Him. Guilt is generally a common factor instigating the act and the choice of the body part to harm is usually meaningful and was seen by the individual as the cause of their sin.4 It is a literal interpretation of several verses in the Bibles that refer to self-mutilation as a way to distance oneself from sin:

29 If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. 30 And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. For it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell.

Matthew 5:29-30

If your hand or your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life maimed or crippled than to have two hands or two feet and be thrown into eternal fire.

Matthew 18:8

Many people who mutilated themselves cited those passages. Reports of such cases can be found in medical books from the late 19th century and early 20th century, during which these extreme cases of mutilation were a source of fascination.1, 4 Nowadays, while rare, similar cases can still be found in people suffering from schizophrenia. Several of them also sought amputation surgically before mutilating themselves on their own.3

imitatio Christi

In medieval central Europe, some very religious individuals called ascetics decided to lead a strict pious life. They would follow a harsh diet, often in a state of semi-starvation, sexual abstinence, and would live in poverty and deprive themselves of any form of comfort such as sleeping on mattresses. Many ascetic people would go as far as harming themselves regularly, integrating the behavior into their daily life, often self-flagellating but sometimes in creative ways to make the experience as painful as possible.5

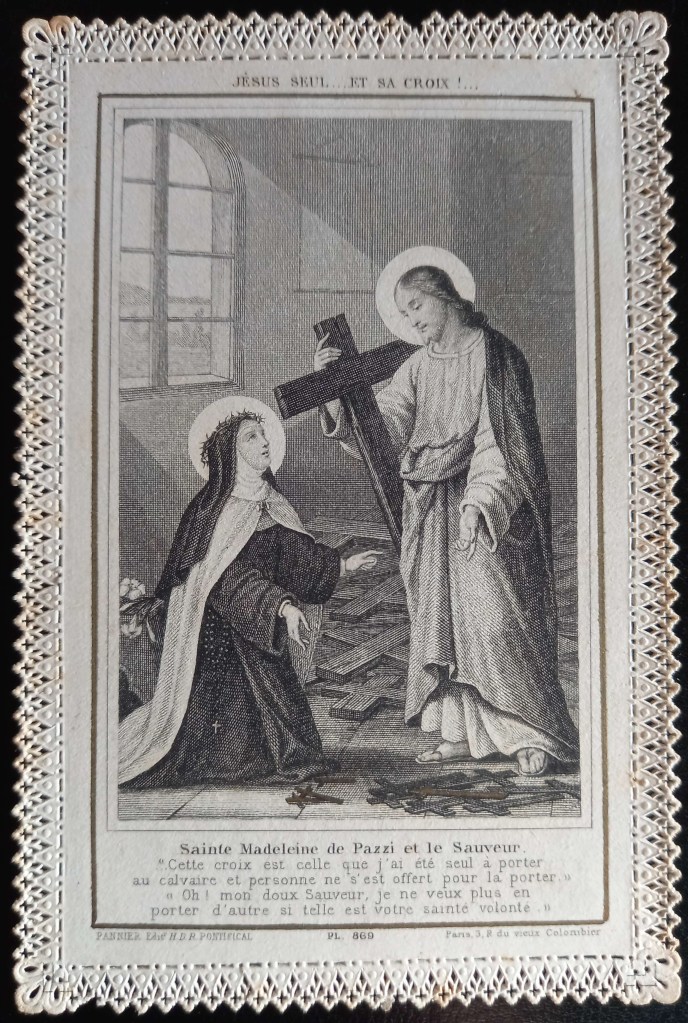

The Middle Age saw an important emphasis on the suffering of the Christ in Christian ideology, and pain was elevated and seen under a positive light.6 For self-mutilating ascetics, the more painful they experienced the greater their love for Jesus Christ and God they felt. Ascetics sought to imitate Jesus Christ in his virtuousness but also in his choice to suffer out of love toward God, through the crucifixion for the Christ and through self-mutilation for ascetics. Self-harm here is not a form of self-punishment: Jesus never sinned and yet he chose pain. It was a demonstration of love for God and a way to get closer to Him by following the path of God’s son.5 Moreover, as medieval christians could not become martyrs like the early Christians, they could prove their devotion by inflicting the pain on themselves.6 Maria Magdalena de Pazzi for example (1566-1607) was an Italian nun who was well-known for her religious self-mutilation. She would, among many other methods, self-flagellate with an iron chain, wear a belt of nails and burn herself with boiling wax.5

Self-flagellation in the Middle Age was not only a personal activity but also a public group practice seen positively. Flagellation was seen by some as the only true way of worshiping and could even replace more established rituals. Flagellant processions spread in Europe and welcomed all classes and types of people, men and women. Unlike written texts that required the interpretation of an educated priest, these performances could be understood by everyone. They quickly became seen as a threat by the established Church who accused them of heresy and flagellant processions were banned by the Pope in 1349. It is important to understand that this ban was a political decision more than a spiritual one. Private mortification was not questioned by the Church as it was not seen as transgressive.6

Stigmata

Stigmata is the name of injuries resembling the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ, generally on the hands, wrists or feet and sometimes on the forehead where the crown of thorns was worn. They have been reported since the 13th century and appear on an individual under mysterious circumstances, often along with vision and in a context of fasting.7 Approximately 88% of stigmatists have been female.

A famous case is German stigmatist Therese Neumann (1898-1962). Her stigmata first appeared in 1926 with a wound near the heart and gradually extended to the eyes, hands and feet. The wounds would frequently bleed, generally on Fridays, and occurred 780 times. The wounds never healed nor got infected and could be seen throughout the rest of her life. While no explanation for her stigmata has been proven, her blood has been tested and has been shown to be hers.8

The Catholic Church remains ambiguous about stigmata and does not consider it a definite sign of sainthood. Some stigmatists were even thought to be beaten by demons, while others were seen as saints blessed by Jesus Christ.9 In such cases, stigmata was believed to be created by divine intervention. It is now assumed that, when not an intentional trick, it is caused by psychogenic purpura and / or self-mutilation.

Psychogenic purpura is a little known phenomenon in which an inner turmoil is subconsciously turned into a bruise by the body. In the case of stigmata, the individual’s identification to Christ is so intense that the mind places those marks on body parts where he was injured. However psychogenic purpura is not considered to be the sole factor in stigmata, it is believed stigmatists also sometimes harm themselves on those bruises during a moment of altered consciousness, drawing blood.7, 9 They then have no recollection of their self-harm.9 Dissociation may be partially caused by prolonged fasting that stigmatists often endure, and it is to be noted that dissociative experience is often found in people suffering from anorexia nervosa.7 In many cases of stigmata, it has been noticed that the wounds do not heal, which could be explained by the frequent reopening of those wounds in unconscious self-mutilation, along with the deficits of protein, iron and zinc caused by prolonged fasting.7

Interestingly, stigmata is for stigmatists a subconscious way of coping with their inner turmoil. Several stigmatists may have experienced early traumas.7 Similarly to modern-time “self-harmers”, mental pain is turned into physical pain.

Conclusion

These cases of religious self-harm extend far beyond christianity. Ritual self-harm was performed all over the world for numerous and diverse reasons such as rites of passage, demonstrations of endurance, sacrifices to the gods and mourning.10 Some muslim rituals for example involve self-flagellation as well and Hindus and Buddhists use piercing and burning in some of their rites.9 These cases are interesting as they question our perception of the behavior and of society’s acceptance of some cases but its severe judgment of others. Religious self-mutilation is cultural, and yet in the case of schizophrenics or stigmatists for example, the distinction between cultural self-harm and pathological self-harm is blurry, as is the case of members of cults who joined either because they were suffering from psychological disorders or because they were in a difficult transitional phase of their life. The case of Heaven’s Gate for example is striking as some members performed castration.11 Is there a difference between those members and the Skopsys for example, who castrated themselves for very similar reasons? Does adhering to a more socially-accepted established religion impacts the very nature of the self-mutilative act? Or is it only our perception of the act that differs? While these questions are not easy to answer, they show that self-harm is a complex behavior and that our perception of it can be subjective.

References

1 – Menninger, K. A. (1938). Man Against Himself. Harvest Book.

2 – Trybou, V., Brossard, B., & Kédia, M. (2018). Automutilations: Comprendre et soigner. Odile Jacob.

3 – Schwerkoske, J. P., Caplan, J. P., & Benford, D. M. (2012). Self-mutilation and biblical delusions: a review. Psychosomatics, 53(4), 327–333.

4 – Lorthiois, M. (1909). De l’automutilation: mutilations et suicides étranges. Vigot frères.

5 – Naor Hofri, R. (2021). The Ascetic Measure: A New Category for the Philosophical Analysis of Self-Inflicted Pain as an Expression of Love for God. Religions, 12(2), 120

6 – Chaney, S. (2017). Psyche on the skin: A history of self-harm. Reaktion Books.

7- Fessler, Daniel M. T. (2002). Starvation, serotonin, and symbolism. A psychobiocultural perspective on stigmata. Mind and Society 3 (2), 81-96.

8 – Rolf, B., Bayer, B., & Anslinger, K. (2006). Wonder or fake – investigations in the case of the stigmatisation of Therese Neumann von Konnersreuth. International journal of legal medicine, 120(2), 105–109.

9 – Mullen, Robert F. (2010). Holy Stigmata, Anorexia and Self-Mutilation: Parallels in Pain and Imagining. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 9 (25):91-110.

10 – Gould, G. M., & Pyle, W. L. (1896). Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine.

11 – Roberts, L. W., Hollifield, M., & McCarty, T. (1998). Psychiatric evaluation of a “monk” requesting castration: a patient’s fable, with morals. The American journal of psychiatry, 155(3), 415–420.