Scans of the 1991 NME ‘4REAL’ article are published at the end of this article. They are graphic, do not scroll past the “References” section if you do not want to see them.

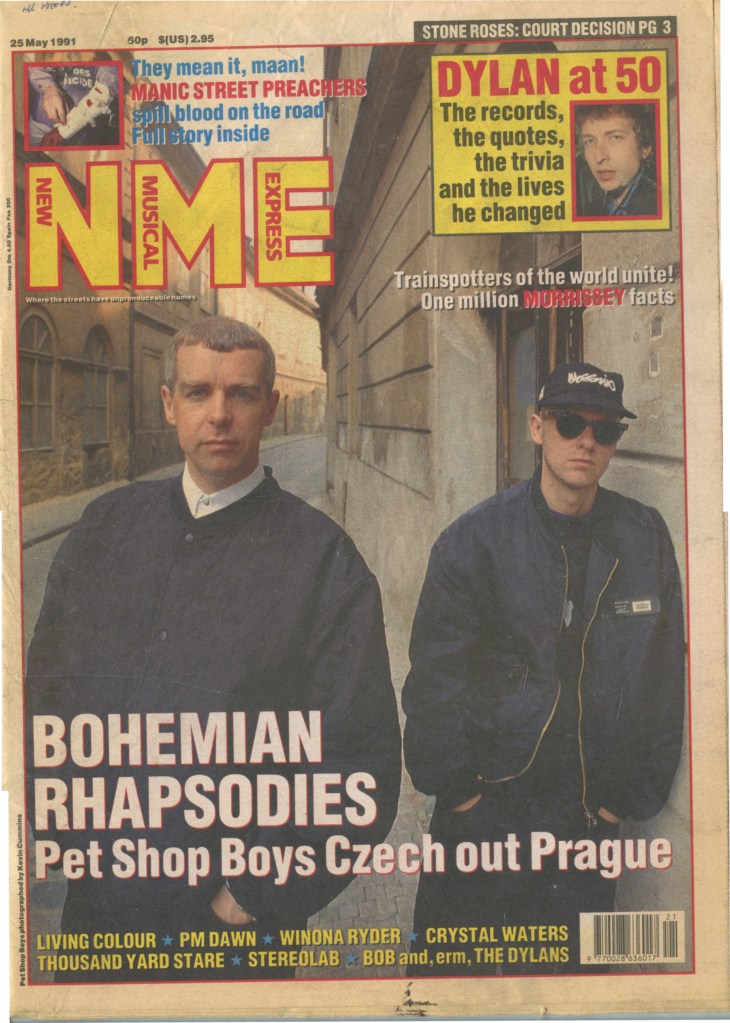

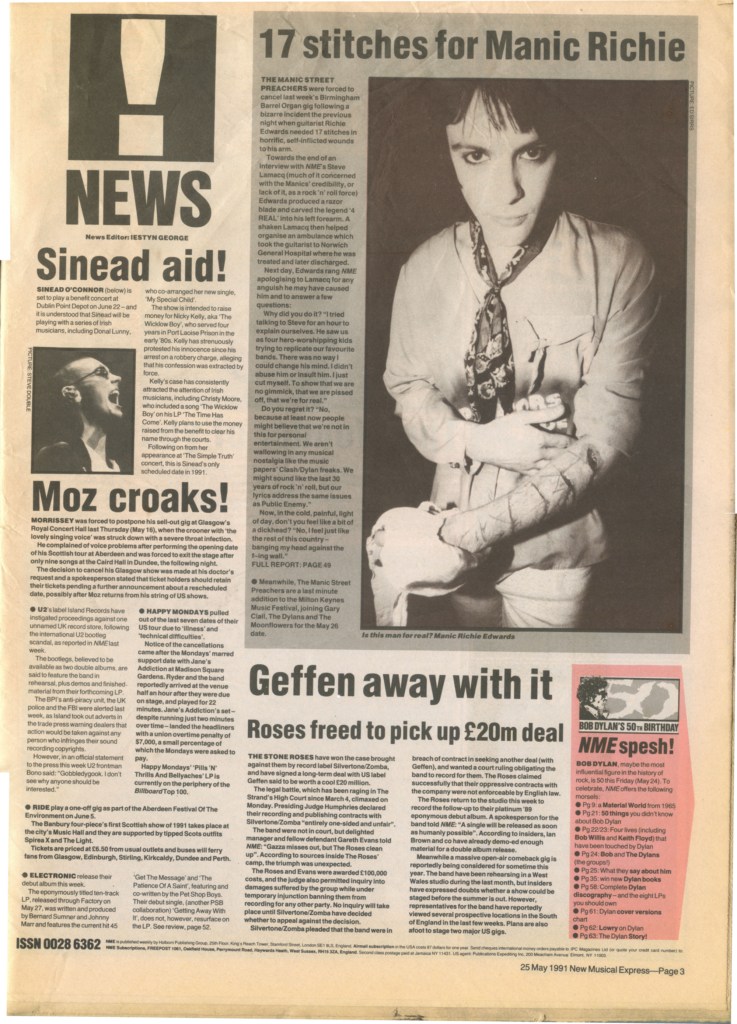

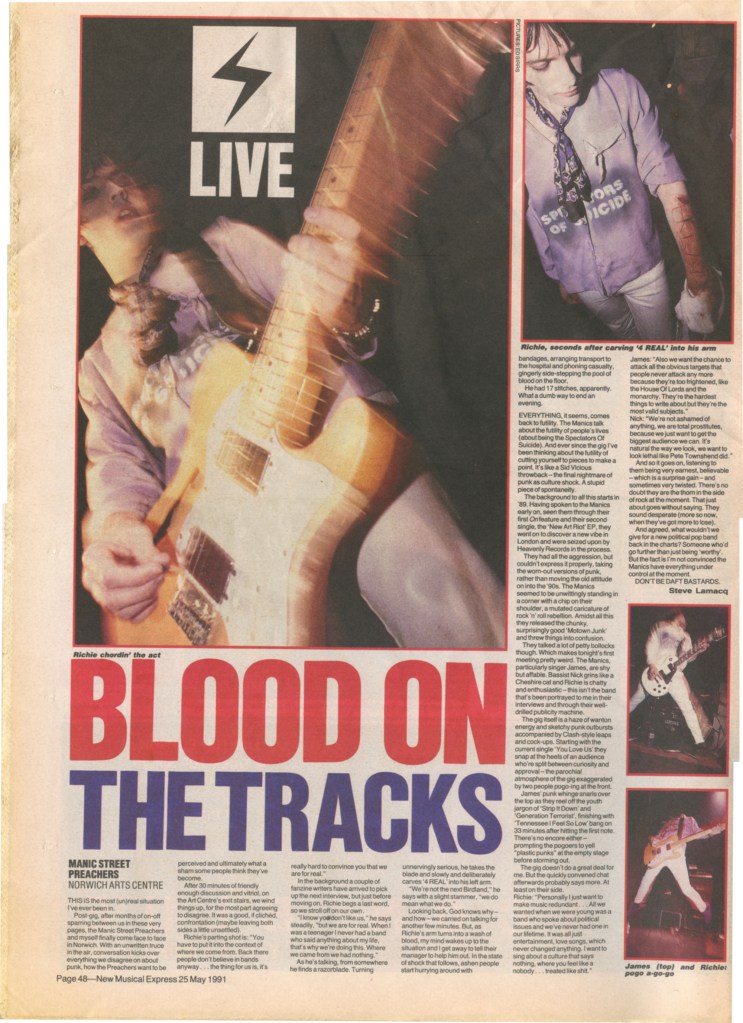

On May 15 1991, Richey Edwards, one of the lyricists and guitarists of Manic Street Preachers, gave an interview to NME journalist Steve Lamacq. As the interviewer questioned the band’s authenticity and claimed they were a marketing product, Edwards took a razor blade and carved the words ‘4REAL’ into his forearm. The injury was then photographed and required seventeen stitches and the event was called the ‘4REAL’ incident. A recording of the discussion of the NME staff about the incident and whether the photographs should be published was released on the Manic Street Preachers’ single Suicide is Painless. This discussion is interesting for it reveals the different interpretations of Richey Edwards’ gesture: some thought it was shocking, that it was self-mutilation and that Edwards was mentally ill, while others were excited and saw the self-injury as “artistic expression”. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is usually a secretive act, performed by the self-harmer to his or her body without the presence of a public. But the ‘4REAL’ incident involved Richey Edwards, his body, Steve Lamacq and more generally the media and its audience. It therefore raises questions about the meaning of Edwards’ self-injury and its impact on society. The 25th anniversary of Richey Edwards’ disappearance and possibly suicide is the opportunity to reflect with hindsight on society’s interpretation of Edwards’ self-harm.

SELF-HARM AS A SYMPTOM OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Throughout his adult life, Richey Edwards would cut his arms and chest and stub cigarettes out on his arms. It is obvious in hindsight, now that Richey Edwards disappeared and probably committed suicide, that his self-injurious behavior was a symptom of mental illness. He suffered from depression, possibly alcoholism and from anorexic tendencies. Therefore, NSSI was a coping mechanism as he explained:

“When I cut myself I feel so much better. All the things that might have been annoying me suddenly seem so trivial because I’m concentrating on the pain…”

Richey Edwards

This reason is commonly mentioned among self-harmers and is coherent with Edwards’ lyrics for the song Yes: “Hurt myself to get pain out”. Another motive for Richey Edwards’ self-harm and also tendencies to anorexia is the idea of control and self-discipline. As he explained, no-one can prevent him from hurting himself or force him into eating. He first cut himself for these reasons, while stressed about exams in university:

“the way for me to gain control was cutting myself a little bit. Only with a compass, you know, vague little cuts, and not eating very much. Then I found I was really good during the day. I slept, felt good about myself, I could do all my exams.”

Richey Edwards

The lyrics in Roses in the Hospital also suggest that self-harm is a way to feel something when experiencing numbness:

“Roses in the hospital

Stub cigarettes out on my arm

Roses in the hospital

Want to feel something of value

Roses in the hospital

Nothing really makes me happy

Roses in the hospital

Heroin is just too trendy”

Roses in the Hospital

We can assume that this song is inspired by Edwards’ experience. Self-harm is compared to heroin, to a way to feel something and to cope with unhappiness. However, as the persona is constantly unhappy and in hospital, we understand that he or she suffers from mental illness, probably depression and that self-harm is a symptom of that illness, similarly to Richey Edwards who was also taken to a private clinic, The Priory, for a breakdown, which failed to heal him as shows tragically his disappearance in 1995.

“IT’S ROCK ‘N’ ROLL, INNIT?”

Richey Edwards’ self-harm was mostly understood as a symptom of mental illness but as Steggals (2013) notes: “the ‘4REAL’ incident could easily have been framed within a well established tradition that connects punk transgression with self-mutilation, a citation of Sid Vicious or Iggy Pop for example”. This is how James from the NME staff understood it, as he can be heard saying, in Sleeping with the NME, “Gosh, you gotta print that, it’s rock ‘n’ roll, innit?” But is it? Is there a difference between Edwards’ self-harm and Sid Vicious or Iggy Pop’s? Are all self-mutilations performed by artists similar (we could add to those already mentioned Pelle Ohlin, Sven Erik Kristiansen, Marilyn Manson etc.) or should a distinction be made between those who performed it only on stage and those who did it without an audience, or those who had a mental illness or committed suicide? Or is it our perception of these acts of self-harm that has changed? According to James Dean Bradfield, a member of Manic Street Preachers, there is a distinction to be made. As he explains, “[s]elf-mutilation in pop, you can trace it through from Iggy Pop to Julian Cope, but they just wanted to be seen as mad fucks”, suggesting that Richey Edwards was not doing it for the same reasons, that is for stylistic reasons. According to Steggals, our own perception of self-harm has also changed:

“The 1990s marked the period in which, socially speaking, self-harm ‘arrived’, or as Favazza puts it ‘came of age (1998), through a process of medical recognition, media concern, and public awareness and in something like the same way that anorexia nervosa had done in the 1980s. And it was this ‘coming of age’ that intervened between Iggy Pop and Richey Edwards, allowing the former to be read as a transgressive punk performer while the latter was read as a troubled soul with mental health problems. Indeed Edwards could be described as a famous self-harmer, both in the sense that he was a celebrity who self-harmed (one of the first to talk about it though certainly not the last), and also in the sense that he owes at least part of his fame to his self-harm and the public controversy that followed it.”

Peter Steggals

Some at the NME staff agreed with Steggals. As they were wondering whether they should publish the photographs of the ‘4REAL’ incident, James remarked that Sid Vicious’ self-mutilation was still not problematic and a man replied that “it’s like rewriting history, doesn’t have any interest”. It could mean that there is no significant distinction between Sid Vicious and Edwards’ self-mutilations but that we should not apply new understanding of self-harm to past events but should however use it to understand recent self-injury behaviors such as Richey Edwards’.

SELF-HARM AS SELF-DESIGN

To expand on the idea that self-harm can be interpreted by some as having aesthetic or stylistic motives, we may wonder if self-harm can be a means of self-design. Whether on purpose or not, “the aesthetics of suicide were become part of the Manics bricolage” (Mankowski, 2013). Indeed, many of their songs were about mental illness such as depression or anorexia and self-harm was often mentioned. Moreover, Richey Edwards was often photographed with his self-harm scars visible, sometimes even fresh cuts and he was open about his mental health in interviews. The song Die in the Summertime opens with the lines “Scratch my leg with a rusty nail, sadly it heals / Colour my hair but the dye grows out / I can’t seem to stay a fixed ideal” which creates a surprising juxtaposition of self-harm and hair coloring, a more socially acceptable body modification. Should both be understood as purely aesthetic attempts at self-design, at achieving an ideal? In the case of Richey Edwards, there seems to be a blur between self-harm and self-design according to Mankowski, but I would suggest that there is something missing in this equation: self-healing. Self-harm is usually an attempt at self-healing, or at least at survival, and so is the case of self-design for Richey. He explained:

“If you’re hopelessly depressed like I was, then dressing up is just the ultimate escape. When I was young I just wanted to be noticed. Nothing could excite me except attention so I’d dress up as much as I could. Outrage and boredom just go hand in hand.”

Richey Edwards

Therefore, for Richey Edwards, both self-harm and self-design could be a coping mechanism. Edwards also had references to his favorite books tattooed on his body. Tattoos are, to some extent, socially accepted carving and both the ‘4REAL’ incident and tattoos consist of writing something on the skin. Self-harm and self-design could be seen as a means of expression.

SELF-HARM AS A MEANS OF EXPRESSION

Indeed, self-harm could be a way to express something that cannot be expressed (fully) through speech. The ‘4REAL’ incident is striking in the way that it is a very textual form of self-harm. It is a message with an author, Edwards, and an addressee, Lamacq and was understood as such among the NME staff as someone noted that “he chose to make his point in that way”. Lamacq explained that before cutting, Richey Edwards said “There’s one last thing I’d like to say”. But Edwards did not say anything, he performed it, he self-mutilated.

“I tried talking to Steve for an hour to explain ourselves. He saw us as four hero-worshipping kids trying to replicate our favourite bands. There was no way I could change his mind. I didn’t abuse him or insult him, I just cut myself. To show that we are no gimmick, that we are pissed off, that we are for real.”

Richey Edwards, 1991

The above quote suggests that self-mutilation is a means to express what goes beyond word, beyond speech. It is a way to express what speaking failed to convey. Richey Edwards often talked about how he had difficulties expressing himself: “I just can’t express what I feel when I’m pissed off”. “I’m not a person who can scream and shout so [cutting] is my only outlet.” Therefore, self-harm might also be a way to release the tension that builds up due to the lack of communication, to the difficulties to express feelings, as suggested in the lyrics of the song Yes “Can’t shout, can’t scream, hurt myself to get pain out”.

RICHEY EDWARDS AS A ROLE-MODEL

As Steggals notes, a “cult” developed surrounding Richey Edwards, especially after his disappearance. This cult seems to be due more to his mental illness, self-harm and disappearance than to his art itself. Some research suggests that “[i]n cases where individuals identify with a model, the risk of imitating that model’s behavior is increased” (Trewavas, Hasking, & McAllister, 2010). This fear of copycat self-harm was the main reason why some at the NME staff were so reluctant to publish the pictures. A woman remarked that “you’ll get all those fans doing the same thing” and that “all you need is for one kid, one child to copy that and kill themselves and you’re” (she interrupted and mimicked the cutting of her throat). Her fear is common. According to Mankowski, the wish for self-design may be acute during teenage years, and teenagers might shape their image on their idols. Indeed, after the ‘4REAL’ incident, some young female fans attended Manic Street Preachers’ concerts “with the words ‘4REAL’ written on their forearms in marker pen” (Steggals, 2013). Skirvin (2000) mentions the case of a teenage Manic Street Preachers’ fan who killed himself. According to his mother and the press he did so to copy his idol, Richey Edwards. Skirvin blames them for their “inability to consider any other motive for a person to take their life other than the influence of a ‘media pop idol’” and while she acknowledges the influence the media and idols can have on people regarding the way they dress, the books they read and their political opinions, she argues that “mass media cannot have a direct effect upon a person, no matter how high levels of exposure are”.

Moreover, Richey Edwards’ influence on teenagers could be positive in the way that he encourages them to develop their own identity at a period when they feel the need to differentiate themselves from adults and also create a sense of togetherness by being part of a community of fans (Skirvin, 2000). Mankowski (2013) suggests that this self-design promoted by Edwards can even be a way for teenagers to distance themselves from negative norms promoted by the media and society. He explains:

“It therefore seems that although certain figures can validate tendencies that may carry risks, their inspiration as models of self-design gives them a positive role, whereas the ill-effects of a blanket culture of advertising imposing unrealistic bodily expectations upon people have been proven by research to be harmful.”

Guy Mankowski

EDWARDS’ FAME AGAINST STIGMA

Richey Edwards contested the depiction of himself as a romantic tragic artist and tried to remind people of the reality of mental illness:

“It’s very romantic to think ‘I’m a tortured writer’, but mental institutions are not full of people in bands. They’re full of people with so-called normal jobs. Or were full. 68,000 beds have been closed down in the last couple of years, which I wouldn’t have been aware of unless I was actually in one.”

Richey Edwards, 1994

Therefore, Edwards’ openness about self-harm might be an attempt at raising awareness of mental health. He was one of the first to talk openly about it which helped many people feel less alone. He was a public figure who talked about private, secret and silent pains such as depression, anorexia, self-harm and alcoholism. He represented people whose illnesses were stigmatized by society, and above all enabled discussion about mental health (Mankowski, 2013). In addition to informing the public by openly talking about such issues, Edwards also enabled those who suffered from these stigmatized issues to feel less ashamed by showing that even “glamorous” idols can self-harm, be depressed or suffer from anorexia (Skirvin, 2000). As a fan of Manic Street Preachers explained “he epitomized everything that people were feeling and gave it a place in the media” (Skirvin, 2000). Most people may have learned about self-harm thanks to the increasing depiction in the media and “[m]usic has been a popular topic of discussion in recent years because of lyrics that feature suicide and NSSI” (Raymond, 2012). Edwards explained his feelings and motives for self-harm in a very simple way. According to Nicky Wire, the song 4st 7lb was written in response to poems about anorexia that glamorized, sensationalized or romanticized that illness. The song is now considered by many anorexics as a realistic depiction of their thoughts, it is harsh, not embellished but straight to the point and is written through the point of view of an anorexic which helps the public empathize and better understand the disease.

CONCLUSION

“You won’t get much coherent sense out of me I’m afraid…” said Steve Lamacq as he was asked to explain the ‘4REAL’ incident. According to Sean Moore, “[t]he only people who are disturbed by Richey cutting himself are those who don’t know him. They don’t understand… We do know him, we do understand.” Do we have trouble understanding self-harm? As we have seen it is a complex behavior with many different meanings, interpretations and motives. It can be a form of self-design, of self-healing, a cry for help, a fight for survival. Richey Edwards was sometimes criticized for his disturbing openness about self-harm but as Moore explained it is only disturbing because we do not understand it. “Self-design can blur into self-harm” (Mankowski, 2013) and this may be the real danger: to see self-harm as something cultural only and not a symptom of pain. Many parents still think cutting is a ‘goth thing’, a behavior that young people copy from their friends, movies or idols. The media and celebrities are indeed often blamed for promoting or glorifying self-harm but this false assumption that people self-harm only because they saw it on TV testifies to the persistent misunderstanding and ignorance about mental health. We must remember that the representation of self-harm in the media as done in the case of Richey Edwards should be accompanied by in-depth discussion in order to understand this behavior and end the stigma surrounding it. To state that a teenager killed himself only to copy Richey Edwards is to deny all the suffering he felt before his suicide. We cannot help people and prevent suicide if we do not first acknowledge they are in pain and have mental health issues. The song Roses in the Hospital might be a symbol of this situation: we bring roses to people in hospitals once they self-harmed or even tried to kill themselves, therefore when it is too late, but the rest of the time we do not want to understand, we stigmatize and ignore others’ pain and mental health issues. Hence their reply: “We don’t want your fucking love”. And indeed, we admire Richey Edwards and see him as a fascinating romantic and tragic figure now that he died but we failed to help him and so many others who were in pain while they were still alive. Let’s now focus on those who are still alive.

Edit 19/01/24: This article has been mentioned in the episode 171 of the podcast ‘Rock N Roll Bedtime Stories’.

References

Mankowski, G. (2013). ‘I Can’t Seem To Stay A Fixed Ideal”: Self-design and self-harm in subcultures. Punk & Post-Punk, 2(3), pp. 305-316.

Raymond, C. M. (2012). Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Movie Industry’s Influence on Its Stigma. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 5(1), pp. 147-166.

Skirvin, F. (2000). ‘Leper cult disciples of a stillborn Christ’: Richard Edwards as meaningful in his fans’ constructions of their identities. Retrieved from theory.org.uk: http://www.theory.org.uk/manics.htm

Steggals, P. (2013). Context and the Problem of Good Understanding. In Making Sense of Self-harm. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Trewavas, C., Hasking, P., & McAllister, M. (2010). Representations of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Motion Pictures. Archives of Suicide Research, pp. 89-103.

Quotes by Manic Street Preachers members are drawn from these websites:

http://www.thisisyesterday.com/ints/ownwords2.html

https://iamiamiam137.wordpress.com/2017/11/29/richey-edwards/

NME, 25 MAY 1991